Chaplains on the Wall

OPINION —

It was a weekend. A lot of people were there. And by “a lot,” I mean folks were standing two or three deep.

It’s one of the most popular sites in D.C. Maybe the hottest spot in the whole town period. The tourist magazines don’t tell you this, but it’s true.

You can keep your trolley tours. Each year, about 5 million people visit 5 Henry Bacon Drive NW to see the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Otherwise known as The Wall.

They come in throngs. You see all kinds. Average suburban Midwesterners, Northern tourists and people with Florida tags, all doing vicious battle over precious parking spots.

People crawl out of trucks, SUVs, and rust-covered economy cars. Old men in battleship hats. Harley guys with military patches. School buses full of kids.

The first thing you’ll be greeted with are signs telling you to download the Wall tour mobile app. Which you’ll want to do. Because, chances are, if you’re here, you’re looking for a name on this Wall.

Last time I visited was six months ago. I was in town for work. I toured in relative silence, reading the names of the fallen.

There, I met a guy who was praying at the wall. He was tall. Skin like mocha. Wearing a white clergyman’s collar. He was crossing himself.

Catholic, I was guessing. Maybe Episcopalian?

He was placing little pink flowers against the wall.

“Lot of people forget about the chaplains in the Vietnam War,” he said. “I come here to honor the chaplains. There are 58,000 engraved names on this wall. Sixteen are chaplains.”

He crossed himself then used his phone to locate the next name.

Meir Engel was the name. A Jewish chaplain who died at age 50.

“He must’ve been like a grandpa over there,” said my new friend, searching for the name. “Fifty years old, dealing with teenage soldiers. They were babies.”

The youngest serviceman to be killed in Vietnam was 15 years old. Chaplains were like surrogate parents to high-school-age soldiers, far from home.

We finally found the name. My friend read a brief biography about Engel. Chaplain Engel was born in Israel, he immigrated to the United States. He left behind two sons.

My friend placed a pink flower at the wall and prayed.

“Military chaplains are overlooked veterans,” said the priest. “We honor the frontline heroes, officers and even rear-echelon guys. But we forget about the holy Joes.”

There were a lot of them in Vietnam.

There was Phillip Nichols. Army. A guitar playing chaplain. Assembly of God. Guys loved him. You didn’t get too many opportunities to sing “Amazing Grace” out in the bush, but Phillip made sure you did. He was killed by a booby trap while traveling between units.

William Barragy. Roman Catholic priest. He was meeting with the 101st Airborne Division. Offering comfort. Distributing the Eucharist. He was killed when the CH-47 he was riding in crashed. He was from Waterloo, Iowa.

Michael Quealy. Army. His superiors advised him not to go, but he did. He had to go. He was a priest, and that’s what you did.

Quealy flew into a hot zone near Saigon. He probably knew he was going to die. He was comforting bloodied soldiers, administering last rites to dying men when he was killed by incoming fire.

And lest we forget Chaplain James Johnson. Army. The only Black chaplain on the list. A special guy.

There were chaplains in Vietnam who accompanied their men, unarmed, on daily combat operations. Who did all this against the recommendations of his superiors because they took orders from a Higher Power.

You would have found them in the fields alongside soldiers every day, listening to young men vent, letting teenage soldiers cry into their chests. Praying with them.

Chaplains followed dying boys onto battlefields, weaponless. Went into hospitals with them, tramped through rice paddies, boarded ships and waded through knee-deep mud alongside them. Some performed baptisms in the yellow water of the Mekong River.

Other chaplains on the Wall I haven’t named are: Don Bartley, Robert Brett, Merle Brown, Vincent Cappodanno, William Feaster, William Garrity Jr., Ambrosio Grandea, Roger Heinz, Aloysius McGonigal, Morton Singer and Charles Watters.

As our tour came to a close, the priest placed the last of his flowers against the wall. “These were good men,” he said.

“It’s a tragedy,” I said.

The priest looked at me. “Tragedy? What do you mean?”

“All these good chaplains, dying like they did.”

He smiled. “Oh, these men aren’t dead, brother. Nobody on this wall is.

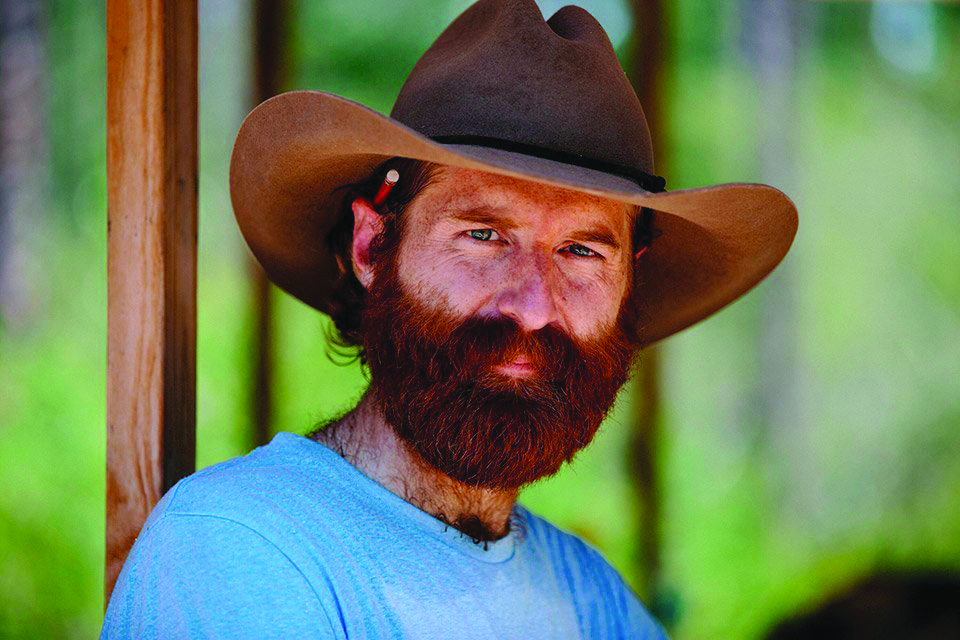

Sean Dietrich is a columnist, novelist and stand-up storyteller known for his commentary on life in the American South. His column appears in newspapers throughout the U.S. He has authored 15 books.