BY SAM HENDRIX,

AUBURN HERITAGE ASSOCIATION

Seventy-five years ago this January, Auburn resident Marianne Jackson Cashatt (1933-2011) was on top of the world: a popular senior at Lee County High School with abundant school and church activities and plans for college. She had no idea the extent a ride to and from Opelika after a school club meeting would change her world. Marianne’s story of faith, determination and perseverance remains monumentally inspiring several years after her death. Today we present the final installment of her story.

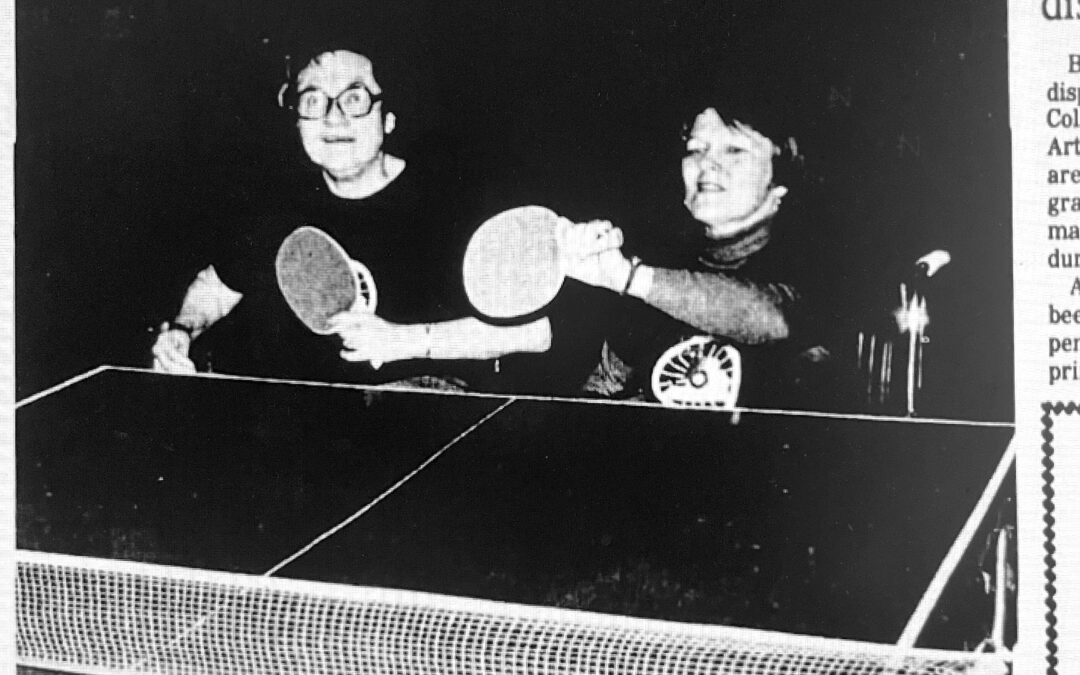

In the 1970s, Marianne Jackson — wheelchair-bound since suffering a severed spine in a January 1950 car accident in Opelika — began competing in athletics events for disabled people. And when those games were held at the Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center campus, as was often the case, she was the lead coordinator for the Center’s hosting the events and their many participants.

In May 1973, Woodrow Wilson hosted the Virginia Regional Wheelchair Games and Marianne had four first-place wins in track and field events. She won in table tennis; in discus with a throw of twenty feet/eight-and-one-half-inches; javelin, with a toss of twenty feet, six inches; and in the sixty-yard dash with a time of 24.74 seconds.

In June 1973, she joined two other staff members and ten students from Woodrow Wilson to compete in the National Wheelchair Games in New York City.

At the Virginia Wheelchair Games at WWRC in early May 1974, she won a sixty-yard dash with a time of 21.73 seconds as well as first place in her class of table tennis. Later that spring, she joined eleven other team members from the Virginia Wheelchair Athletic Association to travel to Spokane, Washington, to take part in the National Olympic Games. She served as secretary of the Virginia Wheelchair Athletic Association that year.

In May 1975, she took first place in both table tennis and in her division for the sixty-yard race at the Virginia Wheelchair Games held at WWRC. Her time in the sixty was 22.30. The next month, competing at the National Wheelchair Games held at the University of Illinois, Marianne took third place in table tennis.

In May 1976 in the Virginia Games, held in Harrisonburg at the James Madison College track, she placed first in shot put with a throw of ten feet/ten inches; third in discus with a throw of eighteen feet, nine-and-a-half inches; first in women’s precision javelin; second in javelin distance with a throw of twenty feet one-and-three-quarters’ inch; and second in another javelin category. She also won the sixty-yard dash in her class, with a time of 21.56 seconds.

As her presence and influence in the world of disabled athletics increased, so did recognition for her efforts and achievements. In 1977, she was selected Virginia’s delegate to the White House Conference on Handicapped Individuals. By 1978, she was a member of the National Paraplegic Foundation, a group formed by paraplegics to battle for the removal of architectural barriers.

In May 1978, Marianne was inducted into the Virginia Wheelchair Athletics Hall of Fame. She was praised for her genuine friendliness, good sense of humor and superb sportsmanship. Also in 1978, Marianne received the inaugural Mary E. Switzer Award, presented by the Mid-Atlantic Region of the National Rehabilitation Association. That year, she also was recognized as Virginia’s Handicapped Professional Woman of the Year, by Pilot Club International. In 1978, she received the Epsilon Sigma Alpha’s Distinguished International Academy of Noble Achievement (DIANA) Award for her contributions to others.

She made her mark beyond athletics as she was the first woman appointed (in the mid-1970s) a deacon of the Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church in Fishersville, a congregation established in 1740. She also later served that congregation as an elder and as an adult teacher.

In 1981, she was named state chair for Virginia’s observance of the International Year of Disabled Persons.

In 1982, she chaired the Governor’s Advisory Council on the Needs of Handicapped Persons. In this role, she spearheaded meetings throughout the state to call attention to the barriers which kept disabled people from taking care of routine business and contributing to society. Perhaps the best example of the needs for which Marianne Cashatt lobbied came in a spring 1983 gathering at the Roanoke County Civic Center, when she needed assistance to reach the speaker’s podium, as the room had no ramp for her to ascend the platform.

Virginia Governor Charles Robb in 1982 selected Marianne as a member of the state’s Equal Employment Opportunity Committee. That same year, she was honored by Handicaps Unlimited of Virginia for service to handicapped citizens. She had previously served on the board of this organization.

In 1983, Cashatt received the Distinguished Service Award by Virginia’s Department of Rehabilitative Services.

Marianne was named Outstanding Employee of 1984 by the Virginia Governmental Employees Association.

In 1986, she served as a judge at the 1986 Ms. Wheelchair Virginia Pageant.

In 1987, she was inducted into National Hall of Fame for Persons with Disabilities in Columbus, Ohio. At the induction ceremony, DRS Commissioner Altamond Dickerson, Jr., who nominated her, said, “Marianne has impacted the lives of thousands of disabled persons through her happy disposition, her eternal optimism and her desire to see people’s lives changed.”

She received two other honors in 1987: appointments to the board of the Blue Ridge Chapter of Multiple Sclerosis Society as well as to the Virginia Board for the Rights of the Disabled.

In 1988, she headed a 25-person committee to oversee Virginia activities related to National Disability Employment Awareness Week, direction of which came from the Reagan White House.

In 1989, she received the R. N. Anderson Award from the Virginia Rehabilitation Association, for outstanding contributions to the field of rehabilitation in the state.

In 1989, she served as president of Shenandoah Valley Kiwanis Club after becoming one of that club’s first women members a few years earlier. That same year, she served as a member of the National Presbyterian Disability Concerns Caucus.

At the end of that year, Marianne let colleagues at the Woodrow Wilson Center know she had decided to retire from her position as director of special services, having worked with the organization for 30 years. She continued her life of service through lobbying and activism on the part of the disabled in the years following her retirement, taking part in the work of several committees at state and national levels. The reality was, neither she nor anybody else noticed that she had retired as she maintained a busy schedule in working to increase disability awareness.

Her efforts over many years helped lead to the Virginia Legislature’s 1990 approval of the Virginians with Disabilities Act. That same year, after she had lent her voice time and again to the needs of disabled people, Congress passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, the world’s first comprehensive Civil Rights laws for people with disabilities. This landmark legislature was signed into law on July 26, 1990, by President George H. W. Bush.

Also in 1990, Marianne received the Pete Giesen Humanitarian Award from Shenandoah Valley Regional Committee for Disability/Employment Awareness for her advocacy for the disabled. At the same time, she was serving on the board of Mid-Atlantic Chamber Orchestra out of Staunton. At various times in the 1990’s, Marianne chaired Virginia’s Disability Services Council and was a member of the State Rehabilitation Council, the Virginia Board for Rights of People with Disabilities and the Board of the Blue Ridge Chapter of the Multiple Sclerosis Society.

In 1992, Marianne was one of 20 people selected as a Switzer Scholar in Rehabilitation. These scholars participated in a three-day, high-level think tank hosted in June by the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities, in Washington DC. This effort was coordinated by the National Rehabilitation Association as a living tribute to Mary Switzer, who directed innovative federal rehabilitation programs 1950-1969 and was vice president of the World Rehabilitation Fund until her death in 1971.

Marianne in summer 1993 traveled to New York City as a member of National Task Force on Life Safety for Persons with Disabilities, bringing attention to the plight of the disabled who are caught in untenable locations during emergencies, such as some victims of the World Trade Center terrorist attack of February 1993.

She co-authored the script for a film, “Olympics on Wheels” as well as a book, Chincoteague Island is for Nature Lovers. In 1996, she was appointed by Virginia Governor George Allen to the State Rehabilitation Advisory Council. She had also been appointed to this committee by Governor Douglas Wilder during 1990-94.

In 1996, she served as vice president of Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center’s Foundation board. In 1999, she was elected to Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center Foundation board as vice president.

Throughout those many years, she was constantly invited to speak at all manner of organizations, from church and civic groups to gatherings of people concerned for the well-being of the disabled. She tried never to miss an opportunity to let people know how they — through their votes, through their volunteering, through their kindness and their influence — could work to make the world more navigable for those with disabilities. And she was hardly limited to traveling a few miles from Fishersville to do this.

“She visited nine foreign countries and every US state,” recalled her sister, Kay Lohmiller. “When she went to China [in 1983, as one of 20 members of the President’s Committee on Employment for the Handicapped], a friend cut a circle in the bottom of her chair because the community bathrooms there were not accessible. She took the board out and went to the bathroom.”

She also made trips, time and again, back to Alabama to watch her beloved Auburn Tigers play football.

“Mom was proud of Auburn,” remembered her son Drew in a 2024 phone conversation. “We followed Auburn through all their sporting events and went down there [typically] two times a year” so she could visit family and friends and spend time in her home town.

On many of her travels back to Alabama, especially after Bill had passed a way, Marianne stayed at the home of her high school friend Margaret Ann Mathews in Montgomery, who often helped Marianne make her way to Jordan-Hare Stadium as she had helped Marianne navigate the steps of Samford Hall half a century earlier.

The obvious question someone might ask about Marianne is, how—given the devastating accident she suffered in 1950 — was she able to find the drive, the energy, the optimism and hope to pursue so doggedly over sixty years the activities she did. One can look to that moment she had, alone, before going to the cafeteria that first evening at Woodrow Wilson, when she committed herself to not feeling sorry for herself again.

Her niece, Katy Leopard, had an informed take on her Aunt Marianne:

“She was the queen of ‘where there’s a will, there’s a way,’” Katy said.

Bill Cashatt passed away from respiratory complications at age 52 in 1980. He and Marianne had been married a quarter-century. She was a widow for 31 years before she died in November 2011 at 78. Marianne and Bill are buried in the graveyard of the Tinkling Spring Presbyterian Church in Fishersville, Virginia.

“She was a devout Christian,” recalled Margaret Ann Mathews. “Her husband was an Episcopal minister, but she never joined the Episcopal Church. She was forever more a Presbyterian. About her accident, she told me once, ‘I know the Lord did not put this on me, but I never could have accomplished what I have been able to do if I had had my legs.’

“The Lord used her and she gave herself to His works,” Mathews said.

Marianne’s sister, Kay Lohmiller, recalled a similar comment.

“At some point, Marianne was writing her last wishes, some thoughts she wanted read at her memorial service,” Kay remembered.

“Her main message was, ‘there were times I could have been resentful. But I would not go back and change having the accident. I would never have experienced the things I have otherwise.’”

Sam Hendrix is the author of Auburn: A History in Street Names and The Cary Legacy: Dr. Charles Allen Cary, Father of Veterinary Medicine at Auburn and in the South.