OPINION —

In June 1977, superstar Elvis Presley was set to perform at the Providence Civic Center in Rhode Island. Tickets sold out quick — too quick — to the two performances. But when a third performance was added, I could have gotten a ticket to that, but I said to myself, “He is just 42 years old, so I can see him in a year or even 10 years when I can afford the ticket.”

Two months later, Elvis was dead. Most of us didn’t know about his poor health. His death from heart failure, due to prescription drug abuse, reminded me of an incident in 1977. I was going to cover a visit by former Vice President Hubert Humphrey. My car had a flat tire, so I couldn’t make it. That was my last chance to meet him, too. Humphrey died in 1978 from a cancer he had kept a secret for two years. He was 66.

This column comes after recent news coverage of the 45th anniversary of Elvis’s death in Memphis, on Aug. 16, 1977. We follow the theme of “Elvis and Me”, a 1985 New York Times bestseller by Priscilla Presley that detailed their life together. Long after his death, memories of Elvis regularly appear in people’s orbit, including mine.

An example of new information on Elvis is the reason he never had overseas tours, despite the money dangled before him. He did perform in Canada, but that is in North America. An Army veteran who served in Germany, Elvis wanted to go back to Europe. But promoter Col. Tom Parker, as shown in the 2022 movie “Elvis”, was opposed as he (Parker) lacked a passport due to legal problems.

Further, it was revealed that Parker was not his real name, and he was not a colonel, either commissioned or honorary. An example from books after his death is the extent of the African American influence on Elvis. It was known he had background singers who were black, and that his song “In the Ghetto” (a hit in 1969) detailed endemic problems in Chicago. But at the time he died, such aspects of his life and career were not emphasized.

After Elvis’s death, the Carter Administration faced a challenge. Statements praising a famous person upon death were almost always used for U.S. presidents, other high-level politicians and statesmen, generals and admirals, sports heroes with contributions outside their sport and innovative businessmen. But President Jimmy Carter knew Elvis, too, was a Southerner and game-changer. He decided Elvis’s broad appeal was worth a presidential statement.

“Elvis Presley’s death deprives our country of a part of itself,” the president said. “He was unique and irreplaceable … His music and his personality, fusing the styles of white country and black rhythm and blues, permanently changed the face of American popular culture … He was a symbol to people the world over of the vitality, rebelliousness and good humor of his country.”

Four instances show how Elvis is remembered in different ways. In 1988, I took my first trip to Graceland. The main thing I liked was buying two original newspapers that announced the singer’s death. “A Lonely Life Ends on Elvis Presley Boulevard” (Memphis Press Scimitar); “Death Captures Crown of Rock and Roll — Elvis Dies Apparently After Heart Attack” (Commercial Appeal).

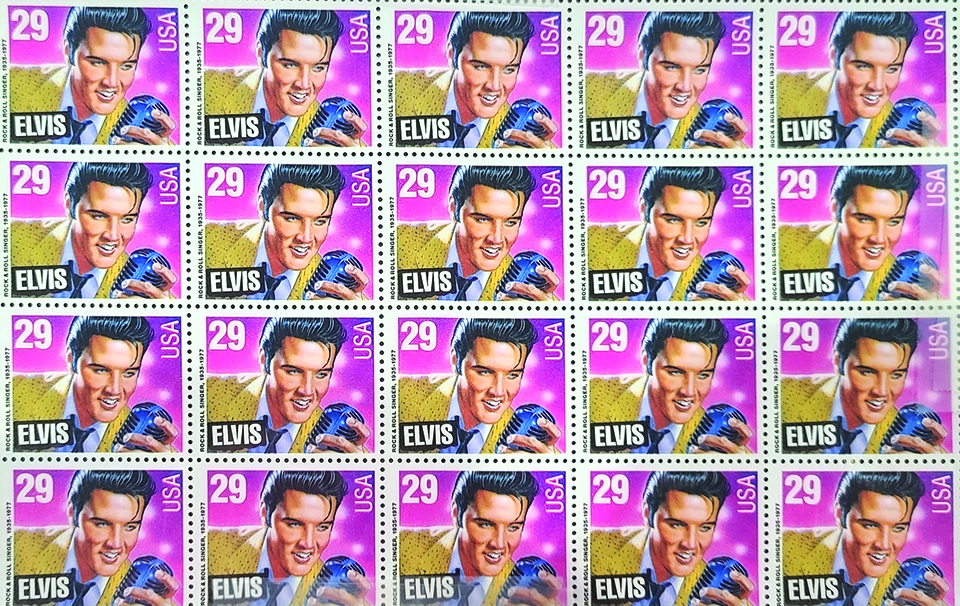

Then in 1992, I was in southeast Germany but still ordered a set of first edition Elvis stamps from a U.S. post office. At 29 cents each for 20, it cost me $5.80. I never used them because they are sentimental; a similar 20 are now worth $85. The third event was when a soldier who knew I liked Elvis made a message board for me.

The front showed that I was in the office, and available for visitors. A happy Elvis was displayed. On the reverse, the words said, “Counseling in progress” and there was an Elvis with a grimace. Whenever I wanted to use a side, I would just turn to the one I desired. (My five subordinates liked the front sign better!)

The final of the four memories was in 2002. We moved into an apartment in East Montgomery and found a neighbor was an Elvis impersonator. There are only 5 million-plus such performers in the world. This faux-Elvis had a pink Cadillac. Most of the time it was covered for protection. His mother said she changed her last name and her son’s to “Presley” when he started to impersonate the singer. That got him gigs as Elvis II (of whom there are only 83,255 in the world).

I plan to attend the 50th commemoration of Elvis’s death in 2027. I missed the 25th, in 2002, which I wanted to write about. This column is not just about Elvis and Me, but Elvis and Us. He was “unique and irreplaceable,” as Carter said. Anybody who disagrees ain’t nothing but a hound dog.Greg Markley moved to Lee County in 1996. He has master’s degrees in education and history. He taught politics as an adjunct in Georgia and Alabama. An award-winning writer in the Army and civilian life, he has contributed to The Observer since 2011. He is a member of the national Education Writers Association (focus-Higher Education). gm.markley@charter.net.