Lake Martin is flat. Mirror flat. It is a perfect evening. The sun is low. The crickets are singing in full stereo. And I’m visiting with old ghosts.

My father would have looked at this calm water and said it was as “flat as a bookkeeper’s bottom.” Only he wouldn’t have used the word “bottom.” He would have opted for a more colloquial expression unfit for mixed company.

Unless, of course, my mother was around. In which case he wouldn’t have opened his mouth at all.

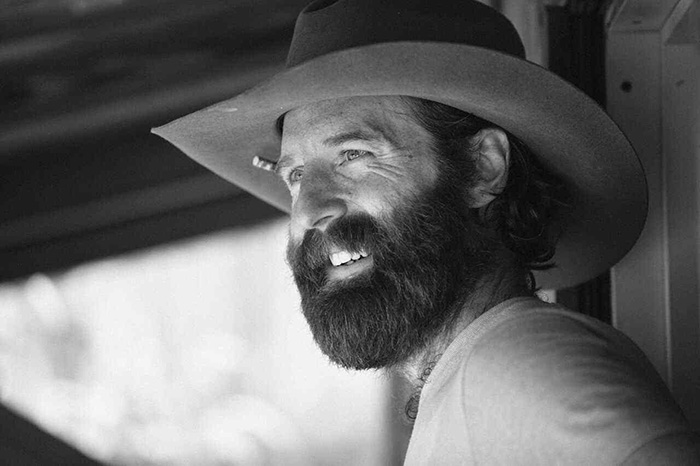

Because he was a man of few words, my father. Which is what I remember about him most. His quietness. My aunt used to say that my father once traveled with the circus, performing as a sideshow act: The World’s Most Quiet Man.

So right now, I’m taking up the family business. I haven’t said a word in a few hours. Mostly, I’ve just sipped my cold glass of Milo’s Famous Tea, and I’m happy in the company of my faded memories.

I am thinking about Granny. Granddaddy. Mama. And the man I once called “Daddy.” I am thinking about what these people would be doing right now, if they were here, alive.

I know what they would be doing. My Granddaddy would be carving a figurine with his butter-yellow Case knife. My grandmother would be reading the Bible, humming hymns and chain-smoking Winstons.

My mother would be sewing something with an embroidery hoop. My father would be shirtless — he was born shirtless. And he would be drinking something harder than Milo’s.

As it happens, I am a big fan of Milo’s tea. I go through three or four gallons each 60 seconds. And do you know why I like Milo’s?

Because they don’t try to do too much with their tea. They don’t dye it red or add weird ingredients like azodicarbonamide, diacetyl, drywall dust or rodent excrement. They don’t flavor it with added garbáge. It’s just tea, plain and simple. Three basic ingredients. Tea, water and enough cane sugar to give your pancreas a workout.

Milo’s is the kind of tea your mother made. The kind you used to have in your refrigerator growing up. Homemade. No frills.

Of course, Milo’s isn’t actually homemade. Milo’s Tea Company is a massive corporation. Last year, Milo’s did approximately $445 million dollars in retail sales. That’s million with an M.

Also, each week, the Milo’s Tea Company sends 35 tons of used tea leaves to the Scotts plant in Vance, Alabama, where they manufacture Miracle-Gro garden soil. Thirty-five tons. That’s approximately the same weight of 10 or 12 average-sized Congressmen.

So Milo’s makes huge money. But they deserve to make millions. Because they make delicious tea. And I love Milo’s. And with all the corporations out there making millions by doing evil stuff, it’s comforting to know there is a company out there getting rich by making sweet tea exactly the way your Aunt Eulah did.

Last year, when the doctors thought I had stomach cancer, I was barred from drinking Milo’s. It broke my heart. Out of all the things I underwent — test after test, scan after scan — the one thing I missed the most? Milo’s.

And so it is, right now, as I sip my sweet tea; as the sun sets, and the air is becoming stagnant; as the hot and humid air makes me sweat like a Kardashian during an altar call, I am glad.

I see a small fishing boat in the distance. I see a young boy, standing on the bow, making a perfect cast. His father — or a reasonable facsimile thereof — is seated behind him.

I hear them both talking. Their voices are reverberating off the water. I don’t hear their words, exactly, but I can hear their tones. Happy voices. Lots of laughing.

I remember fishing with my own daddy. I remember the tone I used when I was with him.

It was a happy timbre. I also remember that I was the one who did all the talking because he was noiseless.

I remember how he’d frequently reach into his red Coleman cooler. I remember how he’d remove an ice cold can for himself. Then he’d fetch a plastic milk jug full of tea, and pour some into a glass for me. He’d throw a few ice cubes into the cup. He’d hand the glass to me and he’d say, “I love you, boy.”

And I don’t know where I’m going with this. I just felt like putting his words in print.