BY SEAN DIETRICH

There is a little girl in my house. She is 11. She is currently playing piano in my office. She is blind, so she plays by feel. She has no idea what she’s doing on the instrument. But she actually sounds pretty good.

I do not have kids. I’m not a smart man, but I am sharp enough to know I’d make a bad dad. So this is unique, having a kid in my house.

Today is a flawless November day. Leaves are falling. The air is dry. My windows are open. Thanksgiving is just around the corner. And it feels like it.

Becca has been staying at our house for a few lazy days this weekend. My wife and I are sort of like Becca’s crazy aunt and uncle. I don’t know how this happened.

I never thought I’d be the crazy uncle who perpetually smelled like Tiger Balm and was always telling children to pull his finger. But there you are.

In her time here this weekend, we’ve gone for lots of walks, Becca and I. Becca usually holds my hand and does all the talking. Somehow, she knows that I have no idea what I’m doing with kids. She can sense that I am not paternal material. But she doesn’t hold this against me.

I was a bar musician whose youth lasted way too long. I grew up in dim lit rooms, filled with smoke, clinking glasses, and Willie Nelson ballads. I used to have a ponytail, for crying out loud.

But Becca doesn’t seem to care. She treats me like I’m a real adult. Which is her first mistake.

Consequently, Becca has done a lot of adultish talking since she’s been here. She has talked about everything from moon rocks to the Battle of Gettysburg. From the invasion of Pearl Harbor to Zacchaeus who—come to find out—was a wee little man and a wee little man was he.

During this brief, 48-hour period, I’ve learned a lot from Becca. I have learned, for example, that tornadoes are caused by warm and cold air. I have learned that the words “wow,” “mom,” and “poop”’are palindromes.

I learned that the Aztecs invented an early form of basketball. The Aztec rules of basketball, however, differ from modern-day rules. The losing team was brutally sacrificed, publicly, and their organs were offered to the gods.

“Brings new meaning to the term March Madness,” I said.

“What’s March Madness?” she asked.

So I have my work cut out for me.

Then, we played outside in the backyard for a little bit.

It goes without saying that I have not “played outside” in many years. In fact, I think Jimmy Carter was president the last time I played outside.

But that’s what we did. My yard is covered in dead leaves because I am allergic to yardwork. Becca plopped down into the blanket of leaves and declared that she was making a leaf angel. She told me to do the same thing. So I did.

And there we were, rolling in the grass and leaves. At which point she crawled atop my chest and said:

“Are you glad you met me?”

“Yes.”

“How glad?”

“Becca, I am making a leaf angel.”

She laughed. Then rested her chin on my chest. “I wish I could see you.”

“You aren’t missing much.”

“How tall are you?”

“Taller than you.”

“What color is your hair?”

“Same color as yours.”

“What about your eyes?”

“They only see you.”

Becca’s birth parents didn’t want her. They abused drugs. So they left her in a crib for the first few years of her life. As a result, the back of her head was flat. She couldn’t walk. She had health problems. It is what medical professionals call “Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome.” What non-professionals call an “addict baby.”

Becca was adopted by two loving parents who have fostered upwards of 30 kids in their lifetime. They gave her the world, and then some. Beck has a good life, full of love.

But she’s been through a lot, and she has scars to prove it. Multiple operations, open-heart surgery, lymph node removals, minor hearing loss, she has Turner’s syndrome. And then came the loss of her vision.

I met her shortly after she went blind. I came into her life one November day, and I don’t know how we became friends. Or why. But she’s the youngest friend I have. And possibly the closest.

When we finished playing in the leaves, we dusted each other off and went inside for supper. We sat at the table to eat.

My wife made macaroni and cheese, roasted turkey and green beans. The kid devoured the mac and cheese. Ate one bite of turkey. Her green beans died of exposure.

But before the meal, we all held hands and said a brief Thanksgiving prayer. The little girl held my hand. Hers were warm. Mine were cold. We all took turns saying what we were thankful for.

She cleared her throat before she prayed. “God, I’m thankful for Sean.”

Well.

I hope someday she raises her standards.

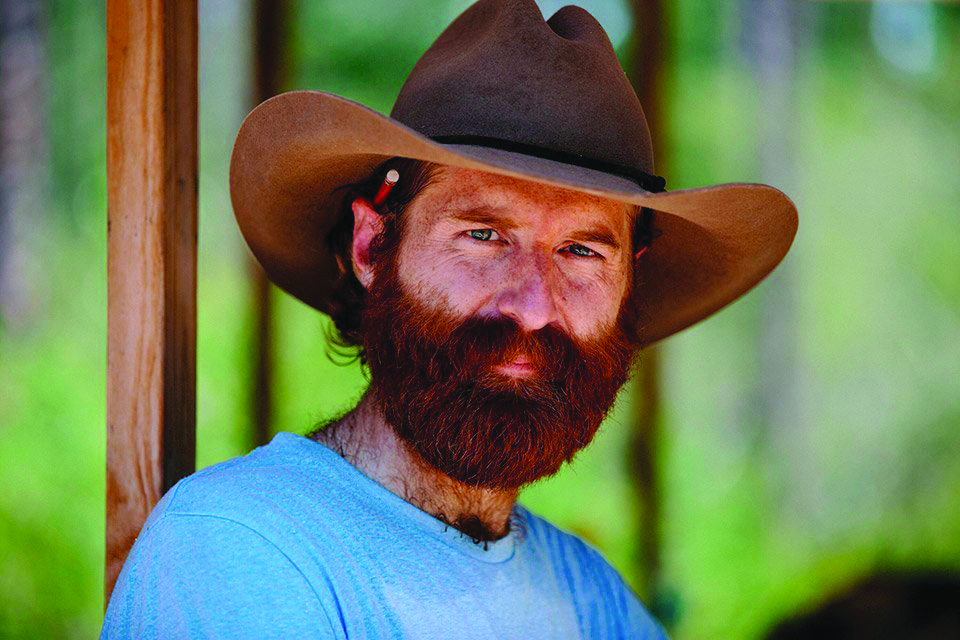

Sean Dietrich is a columnist, novelist and stand-up storyteller known for his commentary on life in the American South. His column appears in newspapers throughout the U.S. He has authored 15 books, he is the creator of the Sean of the South Podcast and he makes appearances at the Grand Ole Opry.