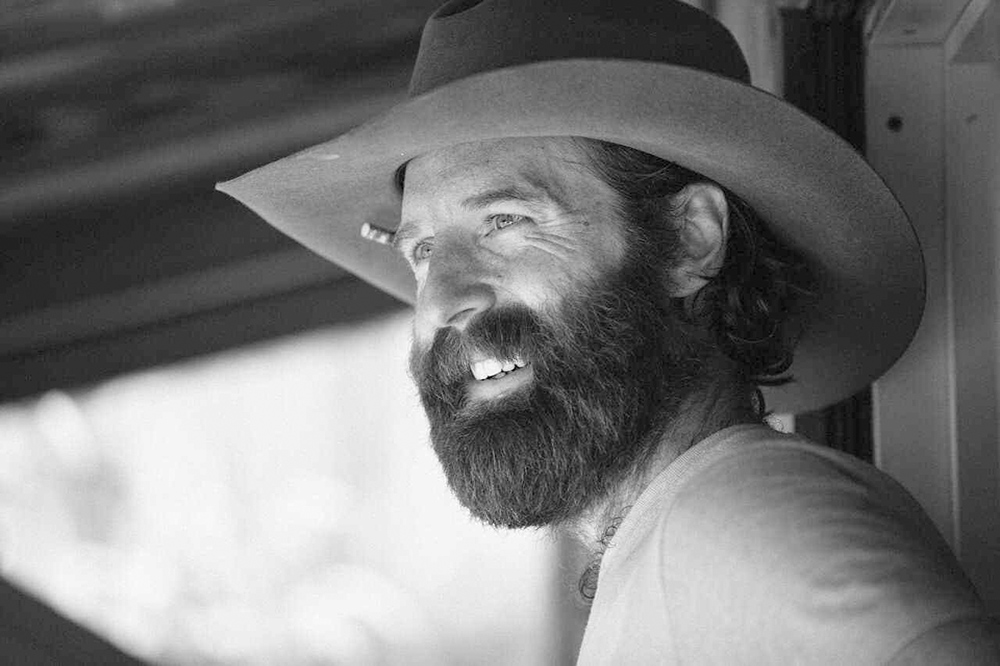

By Sean Dietrich

Dear Malcolm,

I received your handwritten letter in the mail yesterday. It was written so incredibly well. And I wanted to take a moment to write you back. One writer to another.

I wish I had your penmanship. For a fourteen-year-old, you impress me. My writing looks like something that came from the back end of a chicken.

I was excited to hear about your new adopted parents, and how much you love your home with your new adopted siblings. I hope you are happy there. It sounds like you’ve had many good foster parents along the way. I know you miss them.

You mentioned that you recently got a typewriter. I hope you get years of use out of it. I have always been a typewriter man. In fact, the rough draft for this letter is being written on an old Lettera 32. I thought it was only fitting.

So let’s get down to writing business. You asked how to write a story. And even though I don’t have any real advice (since I have no idea what the heck I’m doing) I can tell you a story of my own.

When I was in community college, I took a night course with a bunch of military guys. The classes were held on a military base in a double-wide trailer. We were all adults, and I was the only non-military person in the room.

One night our teacher told us to write a five-hundred-word essay about something we found interesting, then we would read it aloud in class.

And I had a private meltdown. Something interesting? I couldn’t think of ANYTHING interesting. My life was not interesting. And to make matters worse, this was a classroom full of military personnel. Some had traveled to Europe, Japan, Hawaii, out west, back east, up north, around the globe. One man had been to Antarctica.

The farthest I had been was Texarkana.

So I got embarrassed when it was my turn to read my ultra-boring essay. Because my lame paper’s topic was—be prepared to yawn—construction work.

I had written about the time I worked on a construction crew, helping to restore an old beach bungalow in Navarre, Florida.

My essay contained thrilling, edge-of-your-seat details about how beachfront construction was different from inland construction. Roofing materials, for instance, had to withstand gale force winds. We installed windows that were built like M4 Medium Tanks.

My essay was the most uninteresting paper ever composed by a human being. When I finished reading it out loud, half the class was either picking their toenails or engaged in restorative REM sleep.

Everyone knew my work was junk. And more importantly, my teacher knew this.

After class, the professor pulled me aside and said, “I’m giving you another chance to rewrite your essay, because I know you can do better.”

I was humiliated. I had written something so terrible that my sweet teacher couldn’t bear to give me the horrible grade it deserved.

Then she gave me some free advice I will never forget. She said, “I don’t wanna know about renovating a beach house. I wanna know why YOU LOVE renovating it. Put love on those pages.”

At first, I was confused by this. After all, this wasn’t nineteenth century French literature we were talking about. I was writing about construction work. My coworkers were men whose definition of true love centralized on Krispy Kreme and Anheuser-Busch products.

But I promised her I’d give it another try. I stayed up all night rewriting five hundred words. I wrote my essay on this very typewriter, which still has a crooked space bar from when I dropped it thirty years ago.

When I re-read my work in class, I almost vomited from nerves. My paper was about the same beach bungalow. Only this time I wasn’t really talking about the house at all. I tried to follow my teacher’s advice and put some oomph into it.

I told the class that after my father’s suicide I had become like an old weather-beaten bungalow. I told them how my bungalow had gone through a few hurricanes, and that I had almost been blown away.

Then, somehow, a kind-hearted builder noticed me. He saw me from a distance, there on the shore, and he didn’t see my ratty clapboards. He saw what I could be.

The builder and his crew replaced my shattered windows, and my wind-battered roof. They dug new pilings, so I could be sturdy. They exchanged my rotting clapboards. They repainted me. They made me strong.

And I guess that is why I always loved renovating that stupid beach house so much. Because there is nothing more wonderful than being put back together again.

All my life, Malcolm, I have felt like an ugly little house. But it was selfless people who repaired me and made me feel beautiful. I owe everything to them. Everything.

When I finished reading, the first clap started in the back of the classroom. And it trickled forward. Even my teacher applauded. I didn’t deserve it. But it was nice of them.

And I learned a lot from that experience. Sadly, I didn’t learn anything that you don’t already know. So I still have no advice for you.

You’ve been through a lot, Malcolm. You know more about life than I ever will. You’re smart. You’re talented. And you don’t need my help. So I will simply give you the words a sweet old professor once gave to me:

Put love on those pages.

And speaking of love. I sure do love you, buddy.

Sean Dietrich is a columnist, and novelist, known for his commentary on life in the American South. His work has appeared in Southern Living, the Tallahassee Democrat, Southern Magazine, Yellowhammer News, the Bitter Southerner, the Mobile Press Register and he has authored seven books.