By SEAN DIETRICH

There are about 5,240 folks living in the town of Brewton. Although last week someone had twins. So, now there are more.

This township has all the things you look for in the quintessential American hamlet. A Pic-N-Save supermarket. Barbecue joints. Muddy trucks parked outside the attorney’s office. The occasional stray dog hanging by the mill.

The train tracks run parallel with Highway 31, which means that diesel locomotives roll right through the downtown like they own the place. On Douglas Avenue, storefronts still line the street like they did when Woodrow Wilson called the shots. There are flowers everywhere.

But Brewton’s masterstroke, if you ask me, is not its clapboard churches, or the begonias on the main drag. Neither is this town’s glory found in its rainbow row of antique and Greek Revivial homes on Belleville, nor its citywide devotion to jayvee sports.

The magnificence of Brewton lies over on Lee Street inside a nondescript brick restaurant.

The humble eatery sits between a vacant lot and a welding shop, almost invisible if you’re not looking for it. There is an American flag flying out front. A few potted plants.

This place is named Drexel & Honeybee’s Donations Only Restaurant, it is owned and operated by Lisa Thomas-McMillian and Freddie McMillian.

This afternoon I swung open the café’s front door and found myself immediately standing in a line of omnivores, waiting to place my order. When it was my turn, I approached the buffet sneeze-guard and was confronted with the kind of food my mother cooked.

The woman behind the counter filled my plate with ribs, mac and cheese, cabbage, okra and scalding hot hoe cakes. There was peach cobbler and, and the tea was so sweet I had to pray away the type-two diabetes.

I asked how much all this home cooking was going to cost me. They said it was free.

“Donations only,” one volunteer said, pointing to an offering box up front. “Everybody eats, don’t matter who you are. We’ll feed you.”

As if on cue a disheveled bearded man at the donation box was placing quarters and nickels into the slot before leaving.

When I took my seat I was pleasantly engulfed in my plate of country fare. You don’t merely eat Southern food, you let it eat you. And if you do it right, you wear part of your meal.

The ribs were messy and fall-off-the-bone good. The okra probably came from someone’s backyard. The mac and cheese would have made an atheist stand up and sing Fanny Crosby hymns.

Miss Connie was seated beside me, sawing her porkchop with a plastic knife. “Yeah,” she explained, “NBC News is interviewing the owners tomorrow. This place is famous. All the major outlets have visited Drexell’s.”

I asked why.

She took a bite and said, “Because Lisa and Freddie are literally feeding the hungry. They feed all people, all colors, all incomes, all denominations, all ages, all affiliations. This place is a rarity.”

Someone else chimed in. “Customers pay whatever they can afford. Some people can’t pay anything. Others have donated several hundred dollars for a single plate.”

I’m going to spare you all the incredible stories that filter through this meek place. There are too many for one column. Besides, better writers than yours truly have already visited Drexell’s and penned far better tales.

But what previous journalists cannot tell you is what my eyes saw this afternoon. And what I saw transcended cookery.

As I ate lunch I saw three youngish kids at a table; I’m guessing two brothers and one sister. The family was wearing tattered clothes. The oldest behaved like father of the outfit. He was young, but he was burdened with responsibility. His shoes had holes in them and I could see his big toes. He was eating with both hands.

I saw a young mother with a child on her hip. She wore flip flops and had grime on her bare feet. Her kid wore a hospital bracelet. I watched this mother revisit the buffet twice because — I can only assume — she was hungry.

I saw an old man lower himself into a seat at the table across from me. He was wearing a mechanic’s uniform, varnished in grease and carbon. His food was piled higher than Mount Fuji.

I saw a girl who entered the restaurant. A teenager maybe. She had long, stringy hair and was accompanied by an older woman. The girl was maybe sixteen, and pregnant. Her eyes looked sad, but today that child ate like royalty.

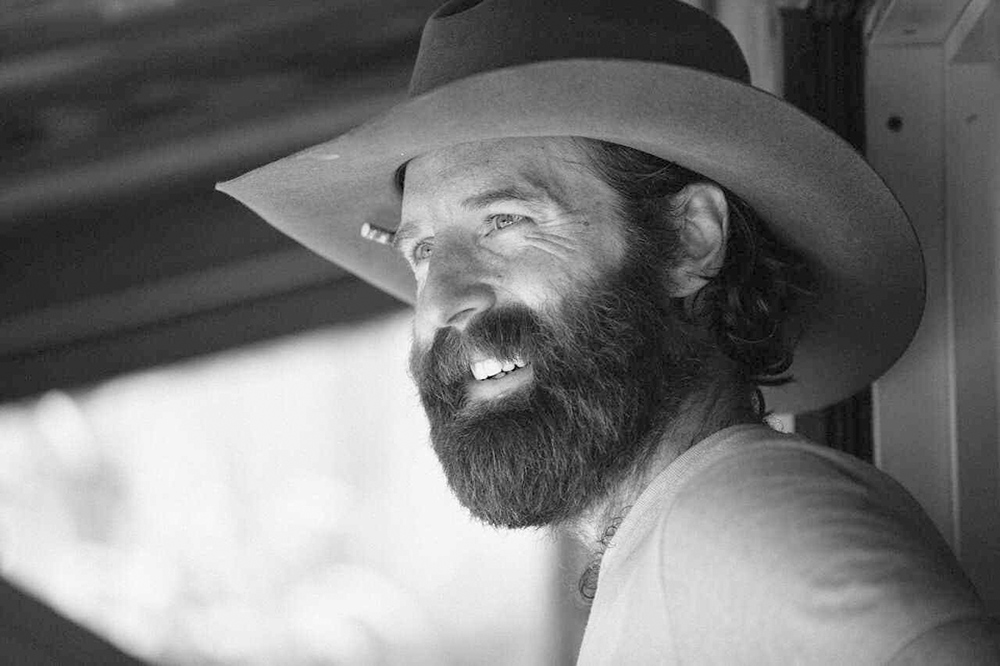

And lest I forget the young man who was seated behind us, so tall and lean he’d have to run around in the shower just to get wet. He was painted in grit and grime from either hard labor or hard living.

The young man removed his hat and said grace over his food silently. I could barely hear his mumbling words, but I saw what was behind those words. You don’t need ears for that.

His hands were folded. His eyes closed. His head bowed over his plate and I could not quit watching. For all I knew this would be the only hot food he would eat today. His prayer was not short, neither was it routine. When he finished his blessing, all he uttered was the word “Amen.”

Try as I may, I cannot think of a more meaningful word with which to end this column.