OPINION —

The last penny has been minted. The humble American “pence” shall be no more. It’s too expensive to produce. It just doesn’t make sense. No pun implied.

The penny costs roughly four cents to manufacture. It’s simply not efficient. The Treasury Department released a statement:

“…Ongoing increases in production costs and the evolution in consumer habits and technology have made [penny] production financially untenable.”

And so, as we march onward, toward a sterilized and cashless world, soulless and artificially intelligent, riddled with “bit coins,” whatever those are, I think about the humble penny. I think of its role in the world I once knew.

The U.S. penny has been produced since 1787. Each penny incarnation has borne different likenesses.

A woman’s head with flowing hair, jingling in the coin purses of Minute Men who carried Brown Bess muskets.

A bald eagle, with wings sprawled, tucked tightly in the money belt of a Californian miner during the goldrush of ‘49.

An Indian head, adorned with ceremonial feathers, resting in the pocket of a Union soldier as he lay dying in a remote field at Shiloh.

The profile of the Great Emancipator himself, used at soda fountains by young men in uniform before shipping out to wallop Hitler.

The penny has been here, almost from the beginning.

Ben Franklin wrote about them. “A penny saved is a penny earned.”

George Washington wrote in a famous letter once: “In for a penny, in for a pound.”

Not to mention all the other well-known quotes about pennies often used:

“Penny for your thoughts.”

“Worth every penny.”

“It costs a pretty penny.”

“Find a penny, pick it up, all day long you have good luck.”

But that’s all over now.

So are the archaic practices of finding a penny on a sidewalk and inspecting the date which is representative of a loved one reaching from across the other side.

I cannot tell you how many pennies I have found which have been emblazoned with my father’s birth-year, 1953, on their surfaces. I found one such penny atop Pikes Peak as I visited his ashes.

The irony is, my dad was a penny pincher. He’d get very bent out of shape if you didn’t save your pocket-change in his gigantic glass jug of pennies. He’d been saving for years.

And one fateful day, when his pitiful-first-basemen-of-a-son expressed interest in playing piano, the old man broke his beloved jug with a hammer. He and my mother sifted pennies on the floor of our garage. Those pennies, that jug, that secondhand piano, they ended up changing my life.

I think of what the penny meant to my ancestors.

My grandparents endured two world wars and a Great Depression. They were impoverished. My great-grandmother earned 20 cents for giving piano lessons. My grandfather worked at a filling station where gasoline was 15 cents per gallon. Tenant farmers like them kept their pennies and dimes in biscuit tins, buried in the backyard.

My father’s great-grandfather came to America from the old country. He was German. He spoke no English, and didn’t have “a penny to his name.”

My mother’s ancestors, Scot-Irish, likely worked in coal mines, dirt farms, sawmills, cotton gins and textile mills, “working for pennies.”

I have always felt linked to my ancestors through the few common practices and items our cultures still share.

Paper books. Porch swings. Checkers. Listening to an old fiddle. Seeing a grandfather teach his granddaughter to dance while the band plays.

Making fresh bread. Building a snowman. Sipping hot coffee from a saucer. Storytelling on a winter night. Baking a turkey, with family in the house. Or finding a lost penny with the date 1953.

I will miss the American penny. But more than that, I will forever miss who we used to be.

Just my two cents.

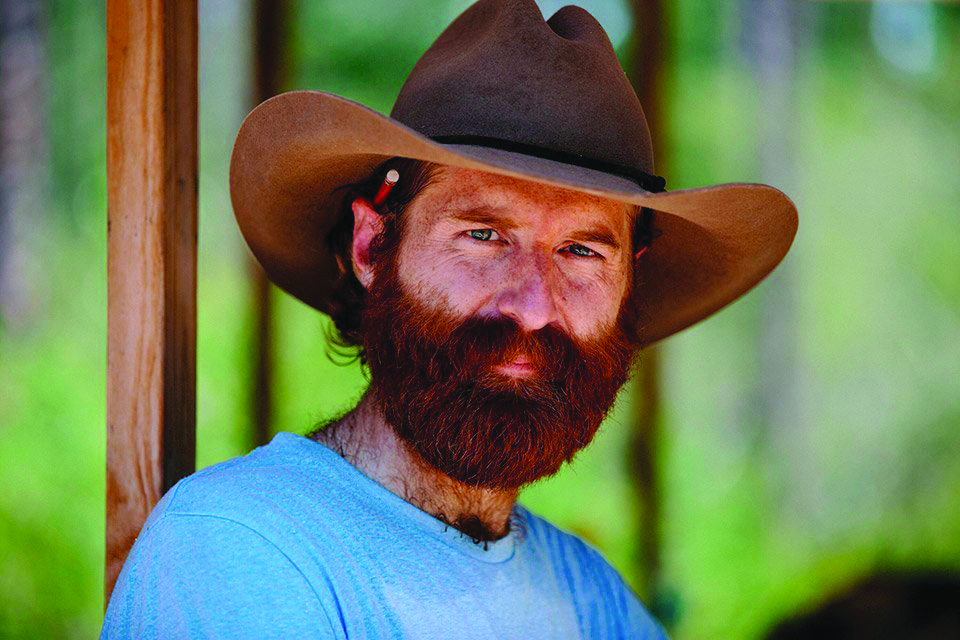

Sean Dietrich is a columnist, humorist, multi-instrumentalist and stand-up storyteller known for his commentary on life in the American South. His work has appeared on “The Today Show” and in “Newsweek,” “Southern Living” and “Reader’s Digest.” His column appears weekly in newspapers throughout the U.S. He has authored 18 books and more than 4,000 columns. He tours his one-man show throughout the U.S., makes appearances on the Grand Ole Opry and hosts the Sean of the South podcast.