By Will Fairless

Associate Editor

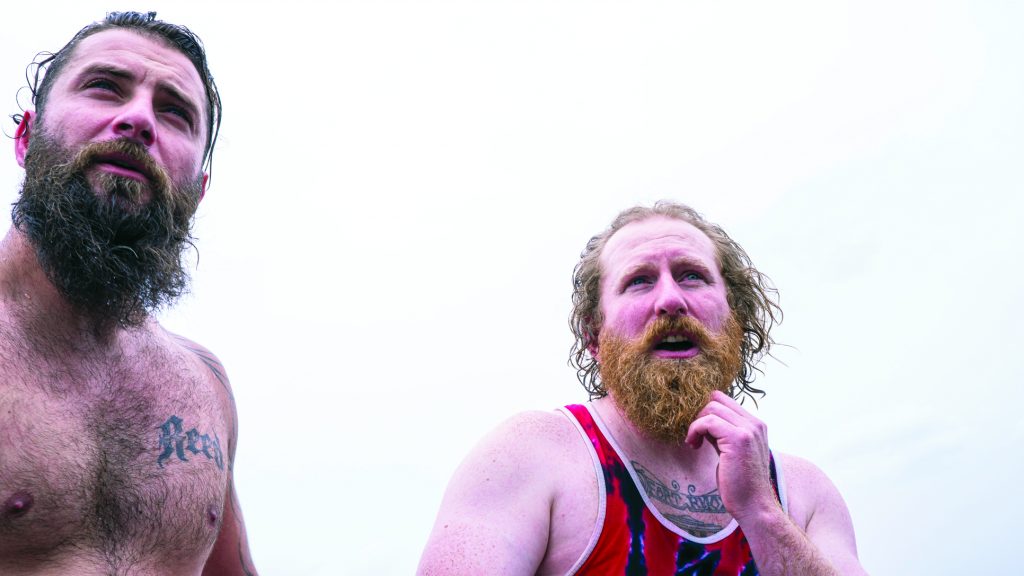

From June 25 to 29, the American Military Family (AMF), on a property owned by The Barn Group Land Trust, held a retreat for nearly 20 veterans who had been experiencing severe mental health issues. Held in Chambers County, the retreat consisted of boating on Lake Wedowee, ATV riding, skeet shooting and evening fireside conversations among the veterans and AMF representatives.

The AMF, through its Got Your Six (GY6) program, helps take veterans, as its slogan says, “from suicidal to successful.” AMF-GY6 is a team of suicide-certified combat veterans who specialize in reaching veterans who are struggling. “Struggling,” in this context, almost always refers to veterans who are planning to commit suicide or have survived a suicide attempt. It might mean, as in the case of Tommy Buchholz, “on his third week alone in the woods of Western Washington in November trying to avoid pneumonia and hypothermia.” It might mean, as in Joey Blackmonʼs story, “just coming off a third suicide attempt, the failure of which he was sure he had prevented.”

According to the National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report, 6,139 veterans committed suicide in 2017, the most recent year for which that figure is available. That number is high (an average of about 17 veteran suicides a day), but it is lower than the annual average of the ten year-stretch before and including 2017. It does not count veteransʼ non-military family members or those who have taken themselves off the grid.

Tommy Buchholz, from Graham, Washington, served in the Marines for five years, from 2003 to 2008, after which he worked for the FAA for ten years; he was then medically retired. “I couldn’t deal with all the mental health issues plus performing that high-functioning job,” Buchholz said. As he put it, “I got lost in [my head], I didnʼt know what to do, I didnʼt know who to turn to or even what questions to start asking. [I thought,] ʻI guess nobodyʼs gonna help me.ʼ”

He set out into the woods by himself to resolve the cognitive dissonance resultant from feeling lost and alone while not being physically lost and alone. Eventually, the AMF got an anonymous call from one of Buchholzʼs friends or family, disproving his alone-and-nobody-will- help theory. The AMF tracked him down, put him up in a hotel and helped him find a job. “I know that if they had not come along, it wouldnʼt have been much longer and I would have been another one of those veterans you read about,” Buchholz said, “Iʼve made multiple suicide attempts in the past.”

Now he works on a 120-acre farm in Washington that was donated for use by veterans. Those working there use permaculture methods to sustainably farm the land; “It literally grounds vets,” Buchholz said, “[It] gets your energy out into something good and healthy.”

Joey Blackmon joined the Army when he was 17 years old, and his unit was activated just after completing basic training. He spent two tours in Iraq as a combat engineer re-tasked to do route security clearance (removing IEDs and other man-made impediments). In the course of that work, the truck in which he was riding hit a roadside bomb, and Blackmon was essentially folded in half inside. “I could eat my bootlaces,” Blackmon said. He added, “That wore a toll on me, but I didnʼt say anything. We were in the Army, we were soldiers . . . nothing hurt me.”

After completing a tour and spending less than a month back in the US, he volunteered to go again to Iraq as part of a special 12-man team accompanying the National Guard. His PTSD, which he did not know he had, kicked in during this stint in the Middle East. He was first sent to Germany for treatment, then to Fort Bragg, where he was placed on medical hold, then was eventually sent back to Iraq. It had been only three months since he was last there.

He intentionally overdosed on the medication he had been prescribed and had to be medically evacuated. That was the end of his military career. “I wanted to be a 20-year veteran,” Blackmon said, “At that age, what the hell was I going to do with my life? Life was over for me.”

He tried everything short of taking his own life to drown out that question, a question ringing in his ears with the volume of a roadside explosive, mangling his mind as violently as an actual bomb had his body. When drugs and alcohol failed, Blackmon attempted suicide by overdose a second time.

At the retreat, he told the story of his third suicide attempt:

“I was sitting on a bridge in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the country because the first two times I had failed, and I wasnʼt going to fail this time. You canʼt stop a train, and I was waiting on that train to come. I knew their schedules, and it wasnʼt but a half a mile from where I was. The train was coming, and I was out in the middle of nowhere. The next thing I heard was, ʻYou look hungry.ʼ It didnʼt click with me. I was out in the country . . . nowhere. I said, ʻWhat the hell are you talking about?ʼ which literally stopped the train of thought . . . and he says, ʻLook, letʼs talk, go for a ride.ʼ I took him up on his offer, started to walk out in front of his truck, and I naturally looked back at his window. And I saw that he was a Vietnam vet, and I lost it. For him to come to me, out of nowhere, it was divine intervention. God had a totally different plan for me and smacked me in the face. Iʼm horrible at killing myself.”

Blackmon now works for AMF-GY6 seeking out veterans who are “struggling” and getting them help. “They canʼt go to the VA,” he said, “because the VA [often has] a 6- to 8- month waiting period, and the guys walk out into the parking lot and kill themselves.”

Retreats like the one in Chambers County help veterans realize that they are not alone and they are not crazy for thinking the way they do, according to Buchholz. “Itʼs a little intense. Talking and getting your story out there a little more, and whatʼs eating you, it ainʼt easy; thereʼs a barrier to get past,” he said, “The first thing you realize is youʼre not alone . . . and the second immediate follow-up on that is realizing there are people who care.”

He added that he and other veterans in similar situations form the habit of bottling up their emotions inside—or of turning to a different bottle to quiet them. A controlled release of those bottled-up demons, made possible by the company of other veterans, prevents the explosions that occur when neither bottle does the trick anymore.

Blackmon said that the veterans who go on these retreats get freedom to open up, and their emotions start coming out. “My team is qualified to actually target whatever trigger point is bothering them, take them to the side, in front of everybody, and work on them,” he said.

His most valuable teammate, in his work with AMF and in every other endeavor, is his wife, Erin. They have been together for 13 years and have two children. She went through her own struggle when Joey came back for good. “I was putting her through hell,” Joey said, “My PTSD was the main cause of her alcoholism.”

Erin’s mission is to bring attention to the mental health needs of veterans’ family members. She plans to finish school soon and earn a psychology degree so she can work with the VA to that end. “I don’t think people understand how this affects the family,” she said, “It affects our daughter, she picks up on it . . . it’s still a struggle every single day.”

On an AMF retreat, military wives and husbands experience the same benefits that veterans do. Just as veterans realize they are not alone in their battle, their spouses discover that their struggle is not unique either. “The wives don’t always understand or know what do to in a certain situation, and they feel alone,” Erin said, “‘Well, my vet does this, my vet does that,’ ‘Well so does mine! He does the same thing, and here’s what I do to help him.’”

Joey sang his wife’s praises: “Anybody that can deal with us is powerful. She holds a lot of weight in her story, and she changes lives, and she helps families, and she’s amazing.” Joey and Erin hope to continue, while fighting their own battles, to help other veterans and their spouses find healing through these retreats.

Scott Smith, President and CEO of The Barn Group, makes his land available for large retreats such as this and has used it for individuals who AMF tells him are in dire need of a mental reset. “We help those that want to help themselves,” Smith said.

Smithʼs contribution, besides the land, is knowing how to use nature to get a person to a point of emotional release, then deferring to AMF-GY6 to take it from there. He admits that he does not know anything about what a military spouse has gone through or what any of the veterans went through by serving, but that he does know how it feels to be needing help and not wanting it.

“Weʼre ATV riding and boating because . . . you will fail at it eventually. So youʼve gotta accept failure,” Smith said, “Theyʼve gotta accept defeat because someoneʼs gotta help them get out of the water or get out of that mud. Thatʼs the key.” The lesson, according to Smith, is that itʼs okay to fail; itʼs okay to get stuck in the mud; itʼs okay to need and accept help. Itʼs okay to be horrible at killing yourself.

“Our goal is to do one of these – a big one like this – every three months,” Smith said, “Eventually, we want to do one every month, but this one is gonna cost $20,000 to $22,000.” It is not for a lack of The Barn Group’s generosity or willingness to help that they cannot hold more frequent retreats, nor is it for lack of veterans in desperate need; the limiting factor is funding. For more information about The Barn Group or to donate, go to thebarngroup.org/donate. To do the same for AMF, go to americanmilitaryfamily.org/donate.