It is a spring evening in West Florida. Humid. The sun is low. I am watching three old men strum guitars and sing “We Shall Overcome” on their front porch. They are singing through a small amplification system for the neighborhood.

“We shall overcome, some day…”

It is a tense world we live in right now, filled with protests, riots, flames and surgical masks. So while these men play and sing, I close my eyes.

The old men are completely tone deaf. But they make up for it with sincerity.

They are ex-hippies with longish hair and sandals. And they have drawn a small crowd. We are all social-distancing, listening to their impromptu jam session.

An older couple sits in a driveway across the street. A young family sits on a blanket in their front yard. Kids linger on bikes, eating popsicles.

“We shall overcome,

“We shall overcome, some day…”

Two older ladies on a porch swing sip from wine glasses. They wear medical masks. One woman spills wine all over her shirt. She laughs, hiccups and keeps on sipping.

Baby Boomers.

The guitarist speaks over the microphone: “I remember going to civil rights marches with my dad. My dad was a Methodist minister. We stood arm-in-arm with people of all colors in Birmingham, we would sing this song.”

They sing again:

“We shall overcome,

“We shall overcome, some day…”

The song itself has been used by billions all over the world. It was once invoked upon the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, by a crowd of 300,000. Martin Luther King Jr. recited it in his final sermon, only hours before he was shot.

But this song is a lot older than that. And I wonder whether anyone listening tonight knows how old this song truly is. I happen to know.

To be fair, the only reason I know the history of this song is because I had to write a college paper about it once.

Well, technically, if we’re splitting hairs, my wife wrote the paper and I just put my name on it.

I was an adult in community college. The assignment was to write on ‘60s protest music. So I asked my wife to help me. She agreed, but only if—this is true—I would pay her $200. In most states, this is called extortion.

What I learned was that “We Shall Overcome” has a few versions. But it officially dates back to 1900. An African American minister, Charles Albert Tindley, wrote a tune named “I’ll Overcome Someday,” which became the basis for the song.

You might not know Charles Tindley, but I’ll bet you know his music. Especially if your mother forced you to attend church like mine did. He wrote, “Take your Burden to the Lord and Leave it There,” and “We’ll Understand it Better By and By.”

Charles was the son of a slave, born in Maryland, before the end of the Civil War. He was raised in an world.

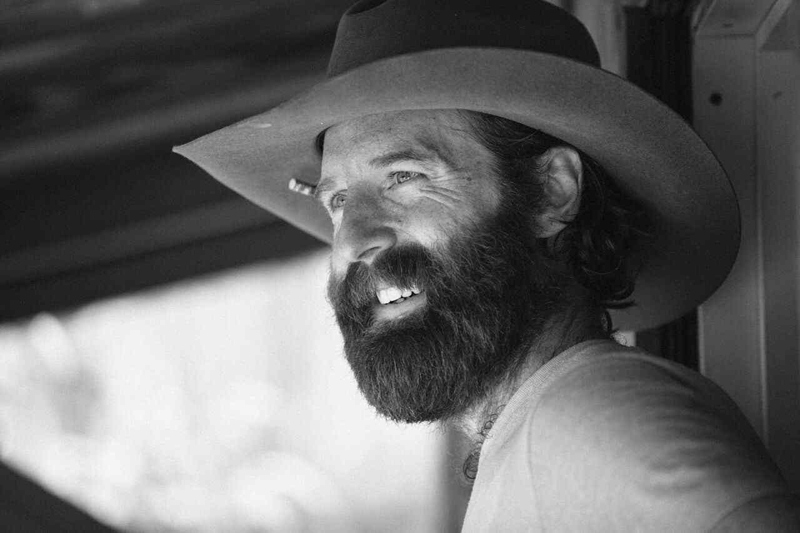

He was a large man, with hands like bear claws, wide shoulders and a concrete jaw. And he was completely self-educated. From childhood, he began piecing together his own education like a mismatched jigsaw puzzle. He taught himself to read, and how to compose music.

As a young man, he wanted to learn Hebrew, so he could translate biblical manuscripts. He went to a local synagogue and begged the old men to teach him. Soon, Charles was reading Hebrew better than the rabbis. Then, just for the heck of it, he learned Greek, too.

Later in life, he got a job working as a janitor at a church on Bainbridge Street, in Philadelphia. It was an unpaid position, so he took another part-time gig, carrying bricks.

Eventually, he applied for ordination. A lot of people said this was a silly idea, since Charles was a manual laborer with no formal education. Still, the Methodist Episcopal church finally agreed to let him take the entrance exam. His test scores were off the charts.

After he was ordained, his life took off like a steam engine. He cared for orphans, fed the starving and helped the destitute along the Eastern Seaboard. Until one day he got a letter in the mail.

The church on Bainbridge Street—where he’d once been janitor—asked Charles to be their preacher. He didn’t even have to think about it. He took his wife by the hand, whisked her back to Philadelphia, and that was that.

In a matter of years, the small congregation of 103 exploded into 10,000. It became one of the largest multi-racial Methodist congregations on the East Coast.

They say the crowds were something else, often overflowing into the chilly streets of Philadelphia, huddling together, clustering on sidewalks, just to hear the giant man preach, sing and speak about overcoming.

On the day of his funeral, there were so many people gathered in attendance that the building’s foundation almost cracked.

Today, Tindley’s church still holds regular services. If you’re ever in the area, stop by. You can’t miss it. It’s the building that’s named after him.

The old ex-hippies finish their musical set. We applaud. They take a bow. I look into the sky. The sun is setting and the crickets are out.

I wonder if Charles can see us from where he is. I wonder if the humble man has been listening to us sing. We are a bunch of average people in an ordinary American neighborhood, singing words he wrote 120 years ago. Because in spite of our faults, we believe them.

If he can’t hear us tonight. He will. Some day.