BY HANNAH HERRERA

FOR THE OBSERVER

OPELIKA — In the winter of 1943, Charlie Plott was in Italy, receiving wine from locals grateful the U.S. soldiers were running “the Germans out of their towns and homes.” He had recently arrived in the country after basic training at Fort McClellan and was about to enter into a deadly land offensive in which most of his company would die.

Nine months before, he and his wife were running Plott’s Grocery on Samford Avenue in Opelika, Alabama and raising their newborn son.

Charlie and Magdalene Plott, a young married couple from Opelika, didn’t see each other for nearly two years during WWII, but they kept in contact through frequent letters. Almost 100 of these letters, along with black-and-white photographs from Charlie’s time in Italy, survived in an old trunk in the family garage.

Bill Plott, Charlie and Magdalene’s first son, compiled those letters, along with photographs and other preserved wartime documents, into a book titled Hello Darling, The World War II Letters of Charlie and Magdalene Plott, 1943-45.

The content of Charlie’s letters range from musings on God, comments on his mother’s whiskey problem, dreams for the future, discussion on the cigarette shortage, remarks that the Italian coast reminds him of Florida and of course, plenty of “I love you’s” to his young wife and son.

But woven throughout Charlie’s casual conversations are pieces of much darker realities.

He was one of only 11 men from the hundreds on the original company roster to survive their first military engagement. An Italian woman hid him on her roof to protect him from a German raid in which his entire platoon was captured except for himself and one other. He was hospitalized multiple times. His two best friends died right after Germany surrendered.

And according to a July 4, 1945 letter and Opelika Daily News clipping, he unknowingly transported Italy’s crown jewels in the back of his jeep across the Swiss border.

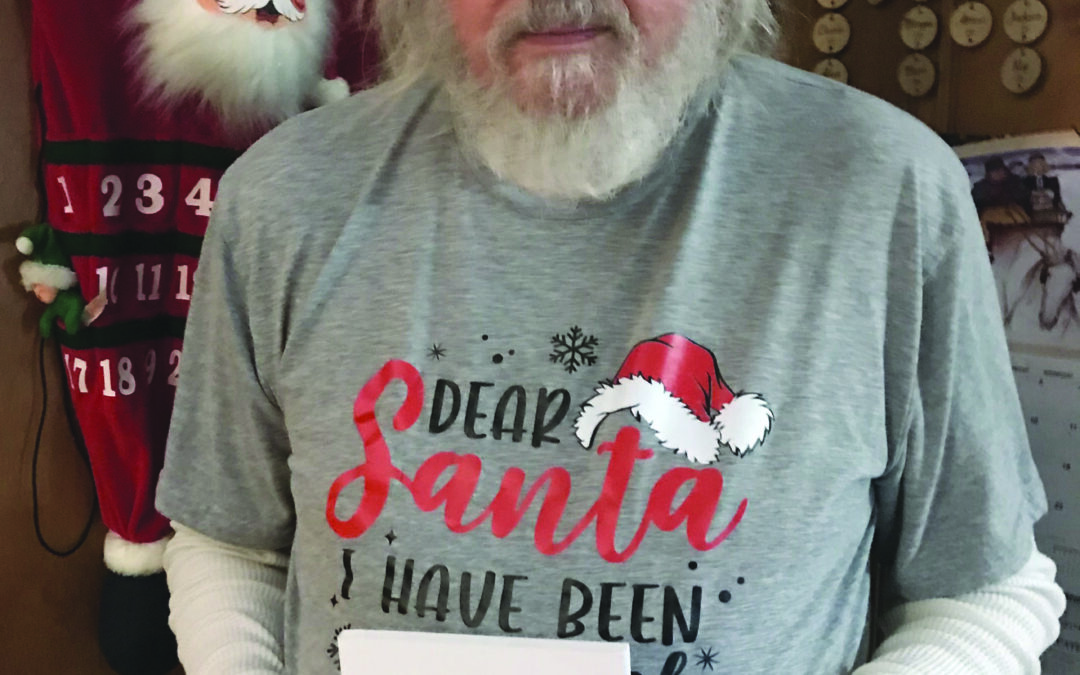

Bill Plott, referred to in the letters as “Billie Joe,” is a longtime Alabama journalist, author and former journalism professor. He said that as a writer, he couldn’t allow his parents’ letters to remain hidden.

“I’m a writer,” Bill Plott said. “I’ve been a writer all my life, so when you’ve got material, it’s hard not to do something with it.”

Fortunately, most of the letters were still in the envelope, making sorting them into chronological order far easier. Bill Plott said he considered editing out sexual references, but his wife convinced him not to, saying it would “remove part of their humanity.”

“I essentially deleted nothing,” Bill Plott said. “All I did was editing in the sense for punctuation and things like that to make sure there was clarity.”

Bill Plott said he was impacted by his father’s tender endearments in the letters, something his mom said had been difficult for him to express later in life.

“Tell Billie Joe that I said he had better be a sweet boy; and as for you, that’s the only way you could be. God bless you and remember I love you.” Charlie Plott wrote in a letter on Feb. 24, 1944.

“[My mom] knew that he loved her, but the just not being able to vocalize it was kind of hurtful,” Bill Plott said. “And I thought, ‘Hell, I think I may be in the same kinda situation.’ And I made an overt effort after that to say “I love you” to people. I think it’s important. It wasn’t that he lost his affection, it was just that mindset then, and I think it was probably a post-war thing after what a lot of these guys went through.”

Bill Plott, who was three years old when his dad returned from war, remembers “being awakened from sleep to see this man who his face meant nothing to me.“

But he and his father soon became “buddies,” and Bill has fond memories of drinking beer, talking and smoking cigarettes together in the back of their store after closing. But there was one thing they never talked about — the war. His father never brought it up, and Bill Plott never asked.

Only once, to his recollection, did he hear his father address it.

“I remember one night at the dinner table,” Bill Plott said, “my middle brother, Jack, who was probably 12 or so at the time, was sitting there at the table and he says, ‘Daddy, did you kill any Germans in the war?’ And I’m just horrified ’cause I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, why’d he ask a question like that?’ Daddy sits there for a couple of minutes, and then he said, ‘Well, if I didn’t, I wasted an awful lot of Uncle Sam’s ammunition.’”

Bill Plott said, if for nothing else, this project was for his family, a window into the lives of their loved ones during one of the most dramatic eras of modern history. And even if his grandkids don’t appreciate their family history right now, he knows they will.

For those outside the family, the letters provide “a little slice of life” into the reality of millions of married couples around the country in the 1940s — years of separation, uncertainty, hardship and the struggle to keep love alive despite it all.

In addition to publishing the letters in “Hello Darling,” Bill Plott plans to donate the letters, documents and photographs to the Museum of East Alabama in Opelika. The book can be purchased online at www.amazon.com/Hello-Darling-Letters-Charlie-Magdalene/dp/B0FR3R9NW1/.