By Fred Woods

Editor

Heroes come in all shapes and sizes. Heroes also react very differently when discussions of their acts of heroism arise. Some will discuss the acts reluctantly if at all. Some even become angry if you push them to comment about their deeds. A few never seem to tire of talking about their actions. And there are some who will even deny that they have done anything heroic.

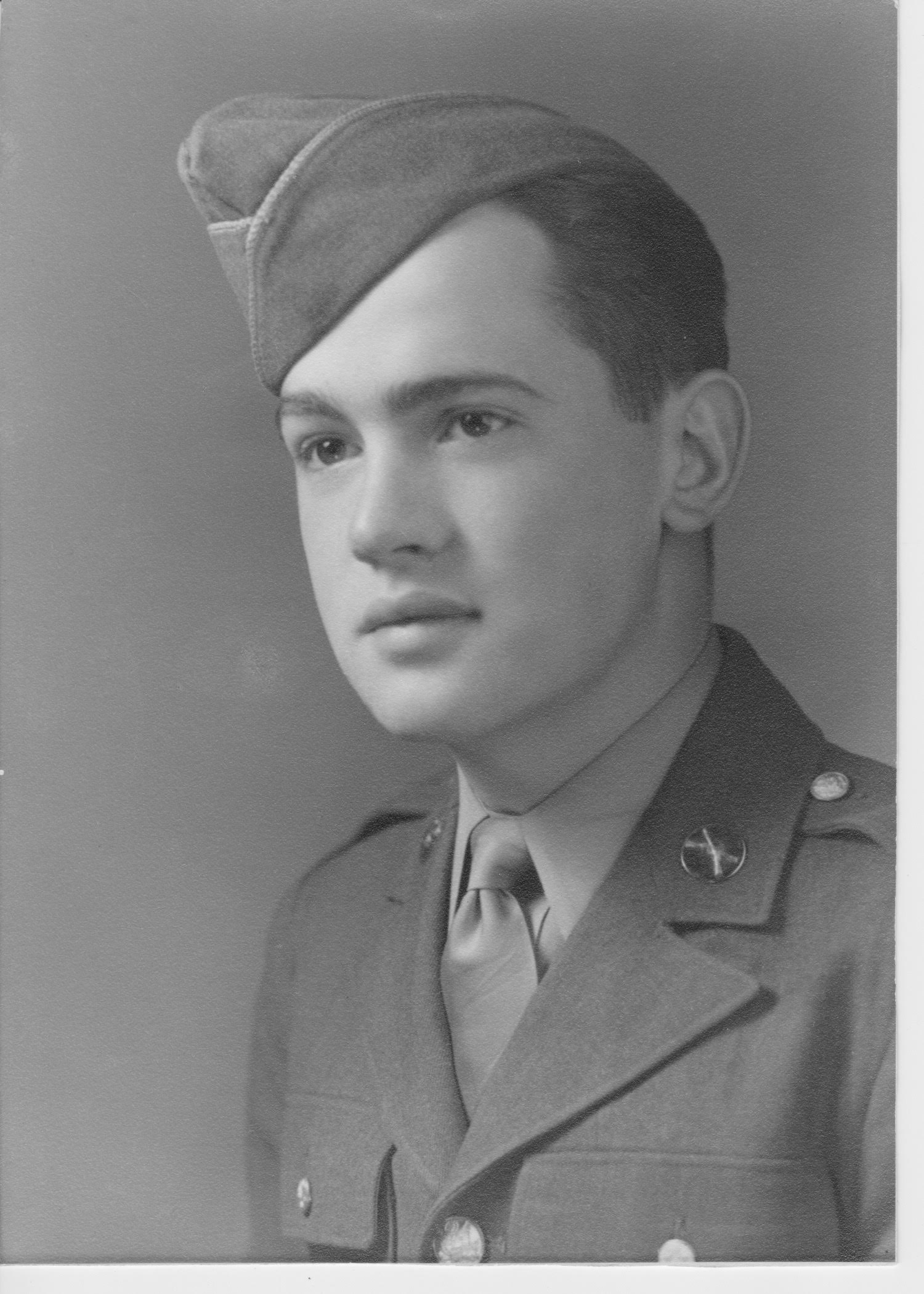

Staff Sergeant John T. Dorsey, Jr., of Opelika (Opelika [Clift] High School class of 1943) received the Silver Star, the U.S.Army’s second highest award for bravery, surpassed only by the Congressional Medal of Honor. Because the citation accompanying the award didn’t exactly meet the facts as John remembered them, he never felt he deserved the medal, that he had been “bought off” to try and keep him from talking about a reconnaissance patrol that had gone badly wrong.

The official citation reads as follows (abridged):

Headquarters 103d Infantry Division

Office of the Commanding General

31 May 1945

General Orders:

Number 156

1 — Award of Silver Star. “ … the Silver Star is awarded to the following named individual:

Staff Sergeant John T. Dorsey, Jr. 34809191 (then Sergeant), Infantry, Company “K,” 411th Infantry Regiment. For gallantry in action. On the night of 13 February 1945 Sergeant Dorsey in the process of leading a raiding party on Niffern [sic], France, was subjected to intense machine gun fire which pinned down his group. Crawling forward he observed the fire coming from the window of a building a short distance away. Turning the assault group over to his second in command, he crawled forward in the face of intense fire to a position directly below the window. Throwing a grenade into the building, he completely destroyed the gun and crew. On his return trip Sergeant Dorsey was fired upon by a hidden sniper. Observing the flash from the sniper’s gun he hunted him down and killed him with one well-placed shot. Sergeant Dorsey’s outstanding valor is in accordance with the highest traditions of the military service. Residence: Opelika, Alabama.”

[End of Citation]

Dorsey’s own account of events sounds considerably more heroic than the official citation. Sure, there are the errors in the official citation, but they have to do with sequence of events, misspelling and omissions that Dorsey viewed as critical but others, including you and me, probably would not.

Dorsey and his group were pinned down by fire from a machine gun that wasn’t supposed to be there and flares which destroyed their concealment. Crawling whenever the machine gun fired and playing dead when it stopped, John reached the space under the window where the gun was firing. With presence of mind to hold the live grenade long enough that the Germans couldn’t throw it back, he tossed a grenade through the open window and killed the machine gun crew. As for the sniper in the next window, John didn’t even remember taking him out but his companions saw him do it.

It was then that the SSG group leader became mentally unbalanced. Dorsey took the necessary action to first restrain and then to calm the agitated soldier down. He then assigned two of the group to keep watch over the man, and sent two others on a reconnaissance to try and locate the other groups.

One group, headed by a lieutenant, was located and the officer, as senior person, made the decision to withdraw. The other group had blundered into the uncharted minefield, losing three of their men, blowing cover for the operation and had withdrawn on their own. Dorsey assigned another four of his men to bear the body of the one group member who had been killed.

Dorsey was angered by the faulty intelligence that failed to locate the machine gun and the mine field, costing a total of four American lives, but as the debriefing officers told him, “Sorry, Sergeant. Nothing’s perfect in this business.”

That didn’t quiet Dorsey’s feelings, however, as he reported that all he felt was a mixture of anger, disgust, frustration and fatigue. All he saw was four dead, more wounded and “… one around the bend and nothing accomplished.” All he wanted to do was sleep.

Dorsey didn’t know he had been nominated for the medal until a couple of months later and had forgotten about it until he was notified about a month after VE-Day (Victory in Europe Day). Dorsey wrote, some years later, that, reading the citation, all he felt was the original frustration and anger, and that somehow his accepting the medal made him complicit in the whole fouled up operation. Yet he kept the medal. He didn’t throw it away. He didn’t send it back.

John Dorsey came home from WWII, went to the University of Alabama for a bachelor’s and a master’s degree and then did postgraduate study as a Fulbright scholar at the University of Paris. He then returned to the University of Alabama where, in 1955, he received the very first Ph.D. degree ever awarded in political science at Alabama.

He taught for several years at Michigan State University until the cold winters got to him. He then moved south to Vanderbilt University in Nashville where he taught until his retirement in the mid-1980s. Dorsey was widely recognized for his teaching and research in the area of public administration with particular emphasis on developing nations.

John died in Nashville in 1993 at the young age of 68. He was buried in Loachapoka.

John Dorsey’s ambivalence about his Silver Star never changed. He came to realize (his words) that the medal symbolized to him what he saw as essentially wrong with armed force as a means of dealing with human problems. In a nutshell, John believed that the military not only exists as an instrument of institutionalized violence, but it seeks to legitimize that grisly function by glorifying it. John Dorsey saw the awarding of medals for valor as a part of glorifying war.

Many people throughout the history of mankind have wrestled with this question. Even so, a notable soldier such as General Robert E. Lee once said, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.” John Dorsey loved his country, that was never an issue. His issue was the futility of war and the possibility that he may have helped to glorify it. But there is no question about it: John Dorsey was a hero, whether or not he wanted to be. John T. Dorsey, Jr., performed heroically in an action he disapproved of as a means of settling human problems.