BY SAM HENDRIX, SECRETARY

AUBURN HERITAGE ASSN.

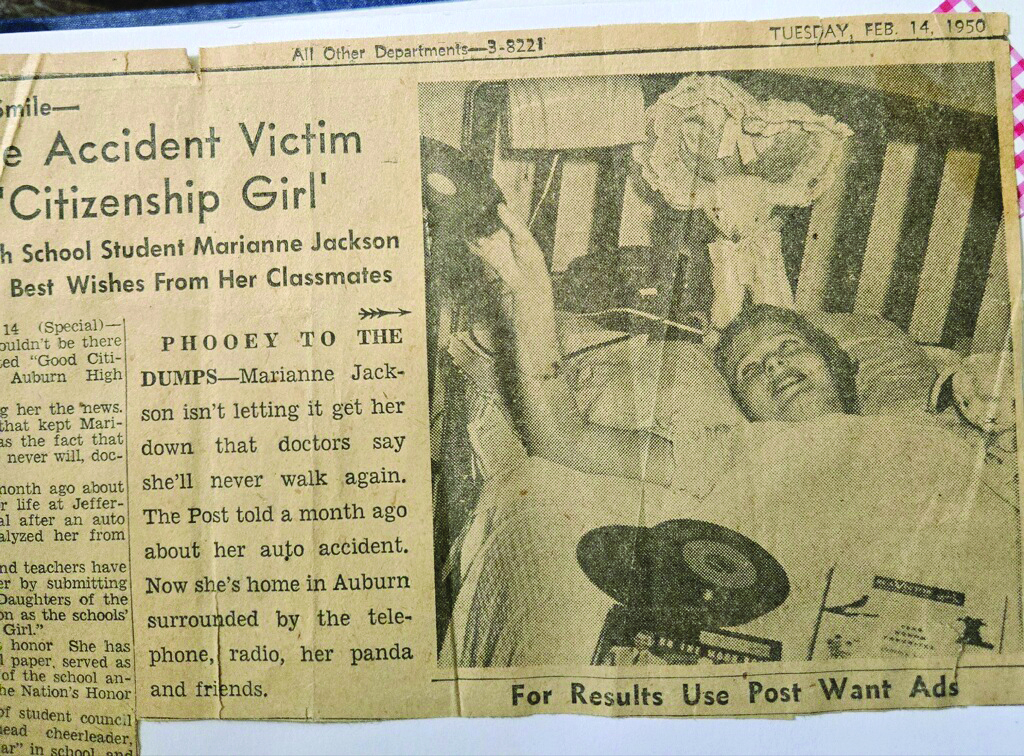

Seventy-five years ago this January, Auburn resident Marianne Jackson Cashatt (1933-2011) was on top of the world: a popular senior at Lee County High School with abundant school and church activities and plans for college. She had no idea the extent a ride to and from Opelika after a school club meeting would change her world. Marianne’s story of faith, determination and per-severance remains monumentally inspiring several years after her death. This is the first of three installments of her story.

Marianne Jackson was Auburn’s “it” girl while she attended Lee County High School during the late 1940s.

Part One

At age 16, Marianne Jackson had every reason to be grateful: popular among her Lee County High School classmates, showing up time and again in the local newspaper’s society column when groups of her friends would have parties. Always included. Loved by all. In Auburn, she was head cheerleader, business manager of the yearbook and a member of the Good Citizenship Club, Student Council and National Honor Society, president of the young people’s group at Auburn Presbyterian Church. Statewide, she was elected lieutenant governor in summer 1949 at Girls State in Montgomery. As a senior, she was voted “Most Popular” by classmates. Had Lee County High named a valedictorian for the Class of 1950, Marianne would have been it.

Growing up in Auburn from the late 1930s, daughter of Pierce Jackson, who operated a down-town sandwich shop from 1932-1945, served in the US Navy’s Seabees during World War II and opened Jackson’s Photo Supply studio at 119 East Magnolia adjacent to Toomer’s Drugs after his return from the war, and Leonora “Nonie” Jackson, who operated a daycare out of the family’s home at 112 Thomas Street, across from Drake Infirmary on the then-API campus. Marianne was respected, smart, charismatic and destined for a full life of achievement.

But popularity and good grades are common. Marianne’s road to significant achievement took an unexpected detour on the unseasonably warm, damp evening of Jan. 10, 1950. Her school’s Good Citizenship Club had met at the Jackson home on Thomas Street. Mr. Jackson and Marianne’s younger sister, Katherine (Kay), had walked to a movie at Toomer’s Corner to give the high school kids room to plot their semester’s activities. After the meeting, the night was young, and the heavy rain of late afternoon had ended, so somebody suggested they go out for ice cream. Six Lee County High seniors piled into Roger Swingle’s father’s new Buick and headed to Opelika, where they filled a booth at The Greens on Marvyn Highway — probably the only place still open that would serve teenagers.

At 8:30 p.m., they paid their bill and returned to their spots in the car. Marianne sat by the passenger window, and Roger Swingle drove. American-made cars in the late 1940s and for several years afterward did not come with seat belts. As the young people made their way over what was then called Opelika Highway, they encountered a wet spot, and Roger lost control of the car. The Buick spun around twice as it crossed the opposite lane — thankfully, no other cars were coming — and crashed into a utility pole. With the sudden stop, the passenger door flew open, and Marianne was ejected and thrown backward into a cement post supporting a picket fence that lined the road. The other primary injury was a broken leg suffered by a boy in the back seat.

When first responders, including highway patrolmen, arrived, they suspected a possible spinal injury, so they carefully secured Marianne to a stretcher and drove her to the Opelika hospital, generously described as a modest forerunner of today’s East Alabama Medical Center.

Back in Auburn, at the Tiger Theater, just before that night’s screening of the musical “Oh, You Beautiful Doll” had its concluding number, Pierce Jackson felt a tap on his shoulder. A theater staff member told him he had a phone call in the Box Office. That’s when he learned of his daughter’s accident. He walked Kay home, made a quick call to a neighbor couple to come stay with Kay and took off with Nonie for the hospital.

Marianne received a blood transfusion that night. A responder, Patrol Officer L. E. Neumann, was the donor. An examination revealed she had sustained broken ribs and significant damage to her spine. Opelika physicians decided to let her rest — without movement — for a couple of days before they transferred her to a better equipped Birmingham hospital. On Saturday, four days after the accident, she was driven to Jefferson-Hillman Hospital, which had opened on the city’s south side in 1887 and remains as the oldest hospital in Birmingham, modernized as a part of the UAB Medical Center. There she underwent surgery. The surgeon confirmed to the Jacksons that Marianne had suffered a complete cut to her spinal cord and would never walk again. In a note published in The Opelika-Auburn News five days after the accident, Pierce Jackson thanked the many friends for “all the flowers and food sent to us.” He also said that while the doctors’ news was devastating, “Where there is life there is hope. God can do anything.”

Optimism, of course, was tempered.

“Marianne told me not long after her accident that the doctors had told her she might have a life expectancy of age 40,” recalled Kay.

A few days after the accident, the Jacksons were making plans to send Marianne to a rehabilitation center, the best one they had identified in this part of the country, down in New Orleans. But it was expensive. The Jacksons were considering mortgaging their home on Thomas Street to pay for Marianne’s lengthy rehabilitation when somebody told Pierce of a far less expensive option in Fishersville, Virginia. The Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center had opened during World War II as a rehab hospital for America’s military members but after the war had been expanded to accept civilians. The Jacksons looked into Woodrow Wilson and decided it would be worth a try.

The day came in early 1950 to take Marianne to Virginia, a drive of a little over 600 miles. Kay and her niece, Katy Leopard, described in summer 2024 how Pierce Jackson had removed the family car’s back seat and installed a chaise lounge so Marianne could lay flat for the journey. The Jacksons all made that first trip and stayed a couple of days to see her checked into the rehab center, but then her parents and sister had to return to Auburn. Everybody was in tears, Kay remembered.

Katy remembered her Aunt Marianne years later, describing those first minutes alone in her room at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

“She said she sat on her bed and cried for an hour, because she felt sorry for herself,” Leopard said. “But then it was time for her to go to the cafeteria for dinner. She got into her wheelchair and rolled herself down the hall. She said when she entered the cafeteria — where she didn’t know a soul — she just sat there for a minute looking around the room. She told us she saw a roomful of people who, in her words, ‘were far worse off than I was.’ She said she decided right then and there that she would never feel sorry for herself again.”

Seven years earlier, an old Auburn dean whom the Jacksons had known from attending the Au-burn Presbyterian Church, had written The Auburn Creed, which by this time everybody in town knew and which included a particularly challenging phrase: “…a spirit that is not afraid…” Whether Marianne realized before January 1950 that she possessed such a spirit, she was going to find out she did. And she would build on that inner spirit and use it to make a difference in her world.

She told a Richmond Times-Dispatch reporter in 1966, “Rehabilitation begins when you stop worrying about what you’ve lost and begin thinking about what you have left.”

Kay said those first few weeks at Woodrow Wilson benefited her sister.

“There, she learned to dress herself, she learned bladder control, she learned to go to the bath-room, to get in and out of her wheelchair and onto a chair, onto her bed, onto a commode,” Kay said. “She learned to drive, and after she came home Daddy had our car outfitted where she could use hand controls to drive.”

She also learned, a high school classmate noted, how to fall and to protect herself in the process.

“She told me early on, ‘those people are mean,’ but she was smiling when she said it,” remembered Margaret Ann Harbor Mathews, who finished Lee County High in 1950 and stuck close to Marianne during their parallel API years.

“Marianne said as part of the therapy and training, they would tell her they were going to walk by and trip her, so she would fall. And then they’d do it, because she needed to brace herself when she fell so she wouldn’t be hurt any worse.” (According to Margaret Ann, the Woodrow Wilson staff would have Marianne leave her wheelchair and put braces on her legs, so she could stand. When she was standing, they would knock her over, to enable her to learn to fall safely.)

Margaret Ann said Marianne learned “how to balance and how to fall. They also taught her to iron the front of her dress, because nobody would ever see the back.”

Marianne began working on strength-training. “She got really strong in her upper body,” Margaret Ann said. “Marianne may have done some weight-lifting because she was constantly having to use her arms to lift herself out of her wheelchair and into bed or to go to the bathroom. She learned up there how to go to the bathroom by herself.”

Half a century later, Marianne would tell a reporter with the nearby News-Virginian newspaper: “When I came [to Woodrow Wilson] I was almost totally dependent. I spent the summer here and I was able to do everything but walk.”

When Marianne returned to Auburn after her first few weeks at Woodrow Wilson Rehabilitation Center, she turned her attention back to completing high school with her class.

Next Week: Nothing can hold Marianne back, as she finishes high school, goes to college, meets a boy and pursues a career.

Sam Hendrix is the author of Auburn: A History in Street Names and The Cary Legacy: Dr. Charles Allen Cary, Father of Veterinary Medicine at Auburn and in the South.