OPINION —

BY SEAN DIETRICH

My interview was scheduled for noon. It’s not every day you are a keynote speaker for Miss Bernice’s fourth-grade class career day, via video call. I wore a necktie.

Miss Bernice’s class has been interviewing a lot of people lately about their careers by using video calls. She has been introducing the kids to people with different occupations from all over the U.S.

So far, her class has welcomed guests from all fields. The class has interviewed PhDs, celebrated journalists, famous musicians, chefs, well-known songwriters, people who work in finance, pro fishermen, doctors, and anyone else who drives a Range Rover.

I was scheduled to go on after the decorated navy pilot.

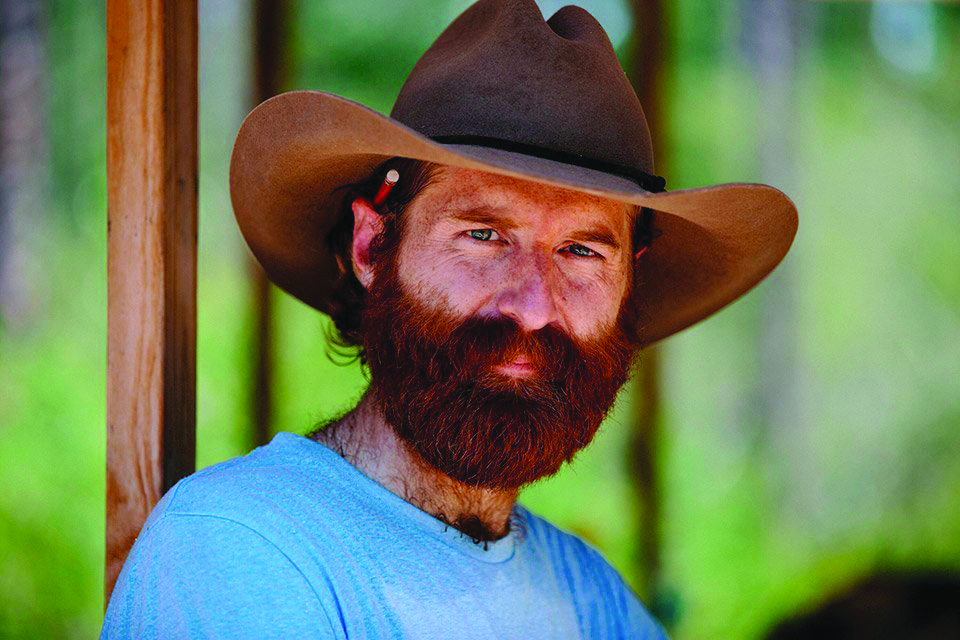

While the fighter pilot gave his presentation, I started to feel like a an idiot. I looked at the little camera image of myself on my laptop screen and cringed. My red hair was disheveled, my face looked tired. The bags beneath my eyes could have been used for a Samsonite ad.

Captain America wowed his audience, and I was trying to remember when and why I became a writer in the first place.

Truthfully, I don’t know when exactly I first wanted to be a writer. I can’t remember ever NOT wanting to be one.

Still, I think it must have happened officially for me in the fourth grade. That was the year our teacher read “Where the Red Fern Grows.”

She would read aloud to us after lunch period, every weekday for an hour. And she did all the voices.

It takes real talent to do the character voices right.

That beautiful woman with the cat-eye glasses and the coiffed hair possessed such talent. I can never forget that period of my life.

We would file into the classroom after gorging ourselves in the cafeteria. She would turn off the lights, sit by the window, and read to us.

Students would gather around her like disciples in da Vinci’s Last Supper. We would lie on the floor, sit at her feet, or recline in her bosom. She would hypnotize us with her voice, and many of us would completely forget about how badly we had to pee.

After she finished reading Wilson Rawls’ classic homily of boyhood, I knew precisely what I wanted to do with my life. I wanted to use little boys restroom.

But also, I wanted to be a maker of stories.

That year I started spending entire weekends before a little pinewood desk in my room, tapping out five-hundred-word pieces on my mother’s manual typewriter. My stuff read like a bad “Curious George” book.

But I fell in love with the process of writing. Namely, because writing was among one of the only acceptable forms of entertainment fundamentalist boys like me had.

I grew up during a slower time. I don’t mean to imply that I grew up in the late 1920s, but I was born at the tail end of an era that still used letters in phone numbers.

The internet had not been invented. Cell phones were devices only found in prisons. Arcade games had pinballs in them. And cable television was for people who told Charles to saddle their horse.

Thus, my boyhood was devoid of technology. The most advanced piece of tech-equipment in our household was my father’s console Zenith television. It was his prized possession. He wiped it down before and after each use.

Entertainment-wise, the highlight of our week was Howard Cosell, or CBS’s “Sunday Night Movie.” We never missed a Lawrence Welk rerun on PBS. And Carson was a deity.

Other than that, it was books for me. I read a lot. And I tried to imitate what I read by typing it onto paper. I adored Doyle, Pyle, Defoe and Samuel Clemens. I idolized anyone who could make me laugh.

But I’ll level with you. I was an untalented student. I wasn’t quick. I wasn’t diligent. I had a hard time following instructions, I couldn’t pay attention. My grades were pitiful. I once lost the regional spelling bee with the word “purple.”

Purple.

Later, I went on to fail the fifth grade. I was almost held back a year, but a charitable educator had mercy on my flailing self-confidence, and she let me enter the sixth grade.

A year later, after my old man died, I dropped out of school altogether and didn’t return until I was a grown man with a mortgage. I was the poster child for white trash.

So how am I qualified to give advice to young people on how to pursue their dreams? How can I, with a clear conscience, impart any words of value when I know so little? How, I ask.

So when the navy pilot finished a stunning presentation for his awestruck audience, it was my turn. I was nervous. It was like being the follow-up act to Elvis.

The teacher asked me to explain to the class how I came to fall in love with writing.

I cleared my throat. And, without preamble, I thumbed open a tattered copy of a children’s book I once read in the fourth grade. A book that has helped me through some very hard times.

I did all the voices.

And I ditched the necktie.