By SEAN DIETRICH

The phone rang.

My wife and I were in the kitchen, cooking an elaborate gourmet dinner. I was chopping garlic. My wife was sauteing shallots or something fancy like that.

My wife answered the phone. I could tell the call was serious because my wife’s face went pale. She was nodding a lot, and doing lots of uh-huhing. A lot of blinking.

Then she started crying. And I mean REALLY crying.

“Uh-oh,” I was thinking. My wife rarely cries. There are only a few things that cause my wife to cry. She cries whenever (a) the University of Alabama loses a bowl game, or (b) whenever someone wears white after Labor Day.

My wife was a Junior Leaguer, back in the day. She follows social rules. She wears pearls and heels to check the mail. She writes thank-you notes for every occasion, including the onset of Daylight Saving Time. And she never cries in public unless “Steel Magnolias” is on TV.

“What’s going on?” I whispered.

My wife shushed me. She plugged her right ear with her finger and pressed the phone into her ear. She was listening intently, nodding rapidly, like the person on the other end of the phone could see her. Lots of yeses and OKs and one-word answers. She was still crying.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

She shushed me again. This time, she waved a 10-inch chef’s knife in my face. When your wife holds a knife the size of a canoe paddle, you tend to listen.

Her conversation wasn’t long. She made a few notes on a legal pad. Then she hung up.

“You’re never going to believe it,” she said.

“Believe what?”

“Guess,” she said.

“You’re pregnant.”

“No.”

“I’m pregnant?”

“Keep guessing.”

I detest guessing games. I used to have nightmares about Pat Sajak.

“Just tell me what the phone call was about,” I said.

She was smiling now. Although her eyes were still glazed with emotion. “You’re going to have to keep guessing,” she said.

I guessed. But I failed.

“Please tell me what this is all about,” I finally said. “You know I hate guessing games.”

She smiled largely. “I’ll give you a hint. It’s about you.”

“ME?”

I felt a pang of dread run through my bloodstream. “Is it good news or bad?” I asked.

“Good.”

“Your cousin decided not to come for Christmas?”

“No.”

“Please tell me.”

My wife wore a serious face. “You know who that was on the phone?”

“Who?”

“That was the ‘Grand Ole Opry,’” she said.

I was silent.

“They want you to come back and perform again,” she said. “On June 10. You’re going to be on the ‘Grand Ole Opry.’”

“What?”

She nodded.

“You’re kidding,” I said.

“No.”

“You’re pulling my leg.”

She shook her head. “I don’t pull legs.” More tears came.

I dropped the knife. Now it was me who was crying. I sort of backed into the wall and tried to catch my breath. I felt dizzy.

Because, you see, I was on the “Grand Ole Opry” last March. It was the biggest night of my entire life. The greatest experience I’ve ever had. I wept onstage. I doubled over and wept.

I shook hands with the Riders in the Sky band. I met John Conlee. I touched the hem of Keith Urban’s blouse.

I thought my Opry appearance was a one-and-done deal. Sort of like getting baptized. You get dunked once, then you’re good for at least a decade. But no, they wanted me back.

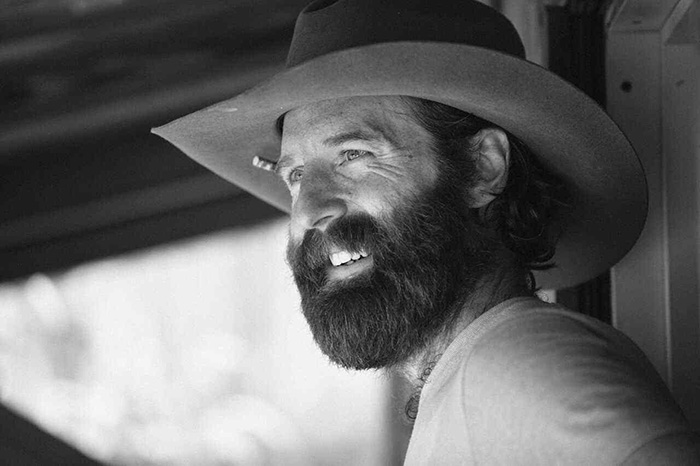

Me. Of all people. The suicide survivor. The high-school dropout. The kid who was raised in mobile homes, camper trailers and cinderblock houses. The guy with a neck the same color as a fire engine.

My wife tossed her arms around me. She held me close. I smelled of garlic and saltwater. We cried into each other’s shoulders.

“You’re going to the Opry,” she said. “For a second time.”

Then she said it again.

We ended up having peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for dinner.