“We were involved in something that nobody in our history had ever been involved in before and that’s reacting to a pandemic.” — Auburn Mayor Ron Anders

By Hannah Lester

hlester@opelikaobserver.com

A year ago, things began shutting down. A year ago, Gov. Kay Ivey declared a state of emergency. A year ago, masks became a common wardrobe staple.

A year ago, no one knew how many deaths would come from this pandemic. A year ago, no one knew how businesses would be affected. A year ago, people could hug their relatives.

Although for the average citizen the COVID-19 pandemic didn’t really hit until March, at East Alabama Medical Center, doctors and nurses were preparing in January.

“We’d started preparing, really with a large, multidisciplinary team to start thinking about what it was going to look like,” said Dr. Michael Roberts, chief of staff at EAMC. “I really felt like by the time we had cases, we were as ready as we could be.”

Of course, no one knew exactly what the response would look like. The hospital was preparing for one or two COVID-19 cases originally, Roberts said.

“There were two rooms in the ICU that we initially had dedicated as our COVID rooms because we were talking about, what if we get one COVID patient? What’s going to happen? Where’s that patient going to go?”

The hospital had it’s first COVID-19 case on March 16 and by the first week of April, there were already 60 patients.

The elective surgery schedule had to be adjusted, visitation was limited and there was a lot of incoming information, Roberts added.

“Once we admitted our first COVID patient, things escalated quickly, and we had to provide alternate care sites to accommodate the volume,” said Amy Rowland, director of Patient Flow & Bed Capacity and Medical Surgical Division. “This included opening a third ICU in our Perioperative area which stopped elective surgeries altogether.”

The hospital had to limit visitation, and nurses had to take on an added responsibility of being there for patients who had no family to visit.

“One of the most difficult parts was separation of patients and families,” Rowland said. “Having to impose visitation restrictions was heart wrenching for us as an organization and was not taken lightly.”

The disease has taken the lives of over 10,000 in Alabama.

“It’s been very difficult emotionally for everybody to deal with, and I think I wasn’t prepared for that aspect,” Roberts said. “We spent so much time preparing for the clinical challenges and the logistics, that that [emotional toll] has been a little bit of a surprise.”

The cities:

As the hospital was dealing with changes, so were the surrounding cities of Auburn and Opelika.

“I actually met with Mayor Fuller and met by zoom with the Auburn City Council just laying out our reasoning for why we felt like it was important to have a mask mandate locally,” Roberts said.

But before Auburn or Opelika could make that decision on their own, Ivey instituted a state-wide mask mandate.

Auburn:

“We were involved in something that nobody in our history had ever been involved in before and that’s reacting to a pandemic,” said Auburn Mayor Ron Anders. “So we had no file to go to, to see how the city of Auburn had dealt with this in the past. We had no one to turn to, to answer the questions and give us good advice. We were literally making up policy and response as it was happening.”

The stakes were high, Anders said, each decision the council made directly affected the people of Auburn.

“Here’s a thriving college community that’s very active in the spring,” he said. “A community in general that is trying to go to spring break and the world changed on a dime.”

Anders said he knew it would be important for him to remain calm and collected as he spoke with residents and made decisions. People were looking to him, and they wanted answers.

“The problem was those good, clear answers weren’t available because nobody had ever had to answer these questions before,” Anders said.

When the pandemic struck Auburn, Anders had been mayor less than two years, he said, but was expected to navigate uncharted territory.

Many decisions were passed down from the state, but before they were, there was pressure on the council to close businesses, Anders said. But, the council didn’t have the authority to shut businesses down before they had done anything wrong, he said.

Ivey announced a state of emergency for Alabama on March 13. Businesses were forced to close and Auburn residents stepped up to the plate to support them.

“The response that our community gave to many of our restaurants as they continue to try to order food from these people, even as it was certainly take out or delivery, I really, truly believe there was committed effort from the people of Auburn to try to support as many of these restaurants as possible,” he said.

The city instituted programs and adapted to the pandemic to continue caring for residents.

“I’m very proud of our city for the way that we kind of changed how we function and we turned a library into an information center, our parks and rec department had a call program for shut-in, older people who were not able to get out to make sure that they were doing okay,” Anders said.

“We redid trick-or-treat so that we could have a trick-or-treat event for our kids, but it didn’t look the same as it’s always looked, but we still provided something for them. And there’s many stories like that where our people changed the way that we normally function to try to provide something relevant to the people who needed our help.”

Opelika:

“I didn’t grasp the long-term ramifications of this,” said Opelika Mayor Gary Fuller. “I thought that it was just some bug that would be around for a few weeks. And of course, it didn’t take long for it to dawn on me that this was quite serious.”

He said that the city moved quickly and began closing city buildings, including city hall.

Fuller said it was hard to watch as places like the parks, the library, the Sportsplex, the basketball courts all closed — and people had to stay home.

Too, businesses had to close to 50% occupancy limits. He said that he even asked some of the big box chains, like Walmart to lower the occupancy to 20%.

The mayor said he looks forward to the days when Opelika Main Street can host events in downtown again and communities can gather.

“I want us to reach the herd immunity stage because I want to see a full house at Bulldog Stadium when we kick of the season in August,” Fuller said.

A year later:

On March 1, EAMC had only 10 COVID-19 hospitalizations and zero patients on ventilators.

“We’re all very hopeful about where we are right now,” Roberts said. “You know, the vaccine distribution, locally, has been absolutely as good as it can be.”

Ivey announced recently that the mask mandate will be dropped on April 9. However, the hospital has announced it will continue to require masks inside EAMC.

“The whole thing has been very polarizing, and I think it’s unfortunate that it became such a political hot-button because I think that was to the detriment of our response nation-wide,” Roberts said.

The chief of staff said that he hopes people will be able to return to sporting events and concerts later this year, but “normal” may be hard to return to.

“I don’t know what normal really means anymore,” Roberts said. “I think there are some things that are forever changed.”

Ivey’s recent announcement allowed restaurants to return to full capacity.

“The good news is, I think we’re not out of it yet, but we can sure see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Fuller said.

Fuller said he believes it will be important for residents in Opelika to take personal responsibility.

“I don’t think we ought to depend on the government to tell us everything we can do and can’t do,” he said. “And even if they say no mask is required, if you’re in a crowded area, I recommend folks wear their masks.”

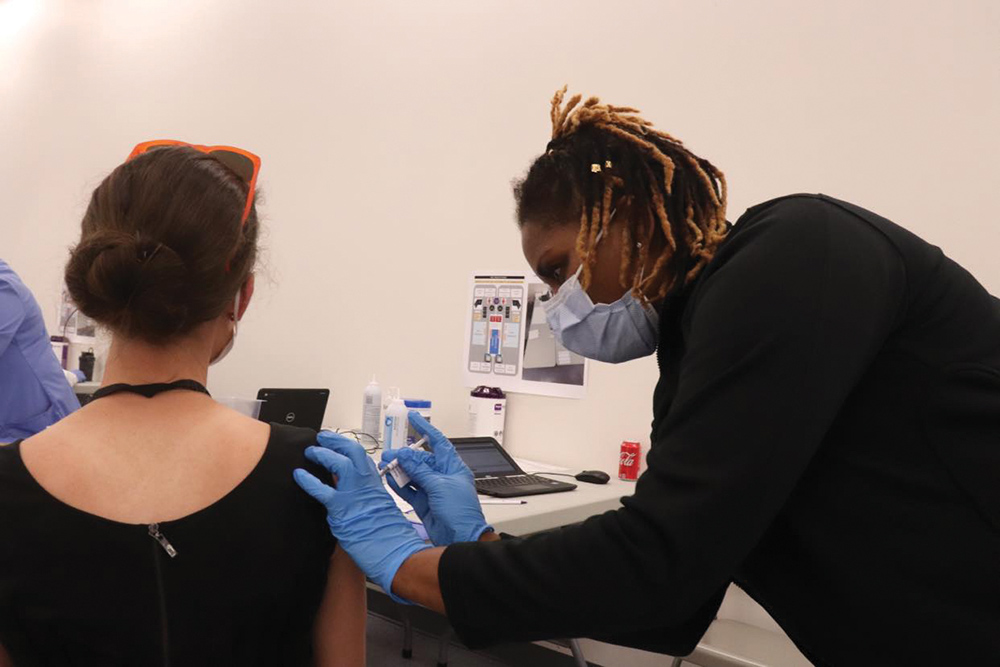

Looking to the future involves vaccination.

Lee County has a vaccination clinic that is working daily to provide thousands of shots.

“At the end of the day, one of the things you’re going to hear from both [Fuller] and I is this vaccine clinic might be one of the greatest moments in our two cities’ history,” Anders said. “As two cities came together with our hospital, and all the support folks from the nursing programs, and Tuskegee, and Auburn and Southern Union to put together a plan of action and a pathway for people to get these vaccines.”

More information about the vaccine clinic can be found on EAMC’s website (https://www.eamc.org/patient-and-guests/covid-19-information/) and anyone interested in volunteering can sign up online (https://app.vomo.org/project/vaccination-site-volunteers.)

While normal is returning, for some families, life is changed forever.

“My heart feels love and prayers continually for those families who have lost people in our communities, that expected those people to be with them today but because of a pandemic they’re no longer with them,” Anders said. “People have made tremendous sacrifices through that.”